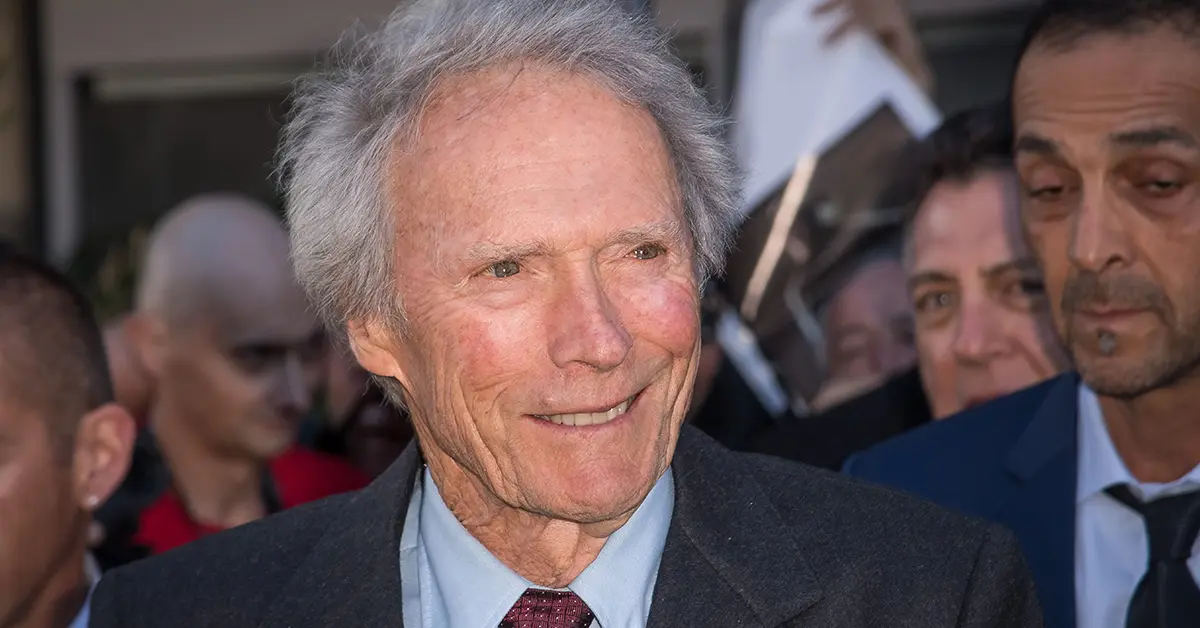

If indeed every movie can be divided into either a comedy or a tragedy, the films of Clint Eastwood have favored one over the other, tenfold. Just over five months from now, Eastwood will celebrate his 93 birthday.

If we zoom out and attempt to observe a specific pattern or trend in his choices, does anything register at all? Are Eastwood the man and Eastwood the storyteller one in the same? That question can be asked of any artist. And the answer is usually a resounding ‘Yes.’ Art is expression, after all—an outlet to release the stuff inside that simply will not emerge in any other meaningful fashion.

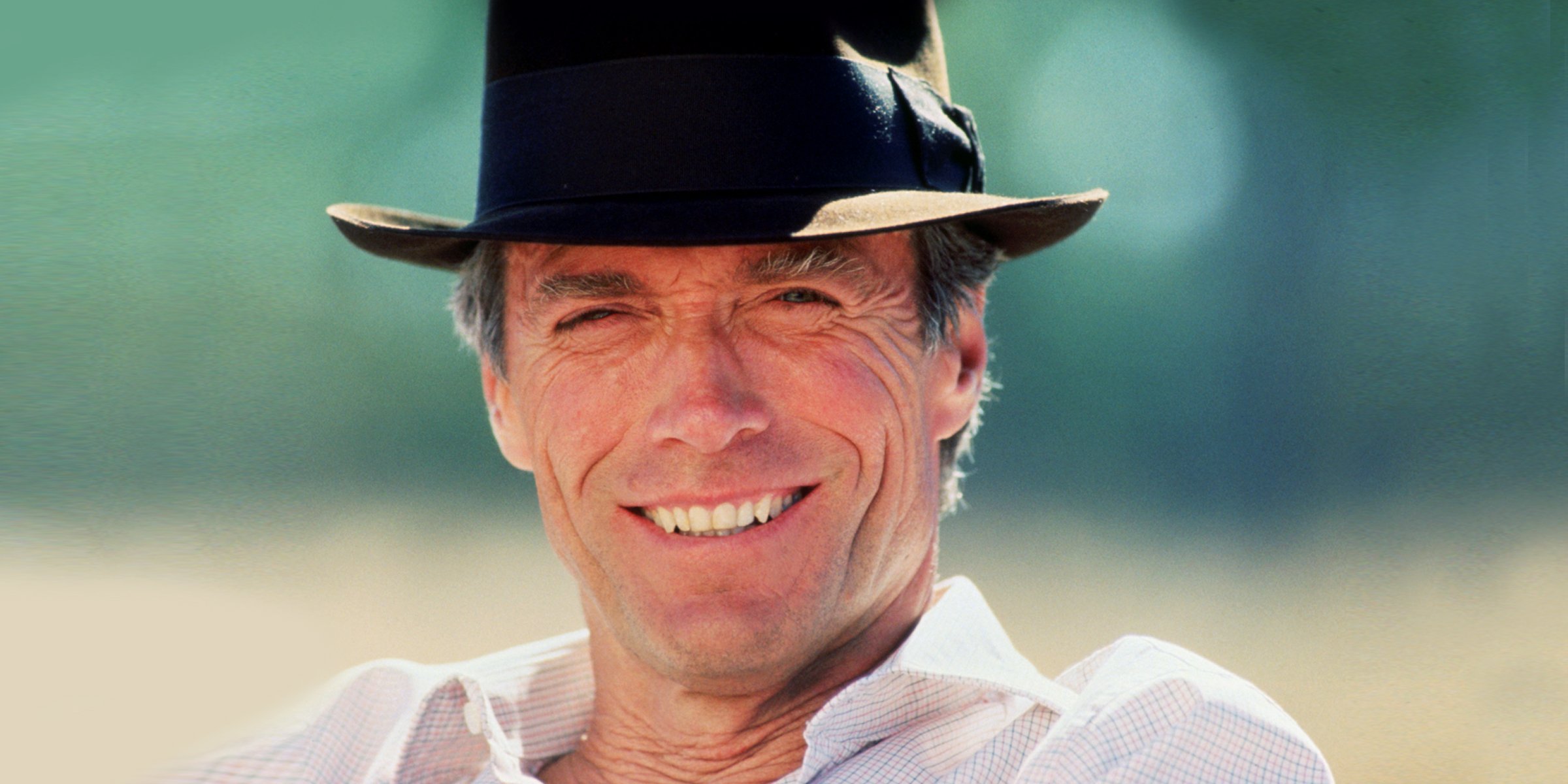

Eastwood the director is an unusual breed. The king of the western (and the spaghetti western) in the 1960s, he first took the reins in 1971, directing himself in Play Misty For Me, a Fatal Attraction-esque thriller about an obsessed fan stalking a radio disc jockey.

It was a departure of a movie for Eastwood, as would become his forte in the projects he would go on to direct. Each would be something different from whatever preceded it. Often directing himself, he’s chosen films that typically put him in some heroic role—a hard-nosed rebel, a mysterious drifter, a tough-talking cop, a tender lover. He also knows when to remain behind the camera, even if the temptation to perform has been present.

To find some consistent element separating his better films from his lesser ones is a tall task. He’s made great movies he hasn’t appeared in, and great ones he has. He’s made biopics and potent contemporary dramas. He’s made war films, and political thrillers—even a methodically paced romance (The Bridges of Madison County). Eastwood is drawn to the non-fiction prestige drama. But he also loves fantasy, which is what the western generally is (and probably the best way to classify Space Cowboys).

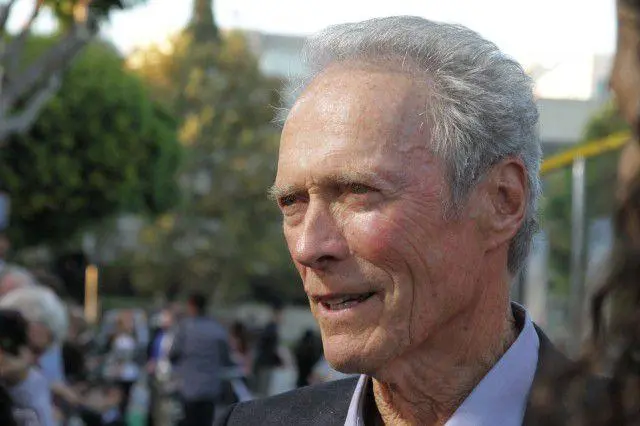

The common denominator among those complex emotions he so loves is this one: sadness. His best movies are rife with it. As a younger man, the tough guy flicks had a certain appeal.

Entering the mid-‘80s and beyond, his choices, while still eclectic, took on different themes and tones. He’d touched on the bittersweet in Honkytonk Man, but 1988’s Bird revealed that Eastwood’s sensibilities and tastes went far beyond what audiences were aware of.

That film, a biopic on jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker (Forest Whitaker) was saturated in tragedy, as Eastwood told the tale of a man of great talent, burdened with great conflict until his untimely death.