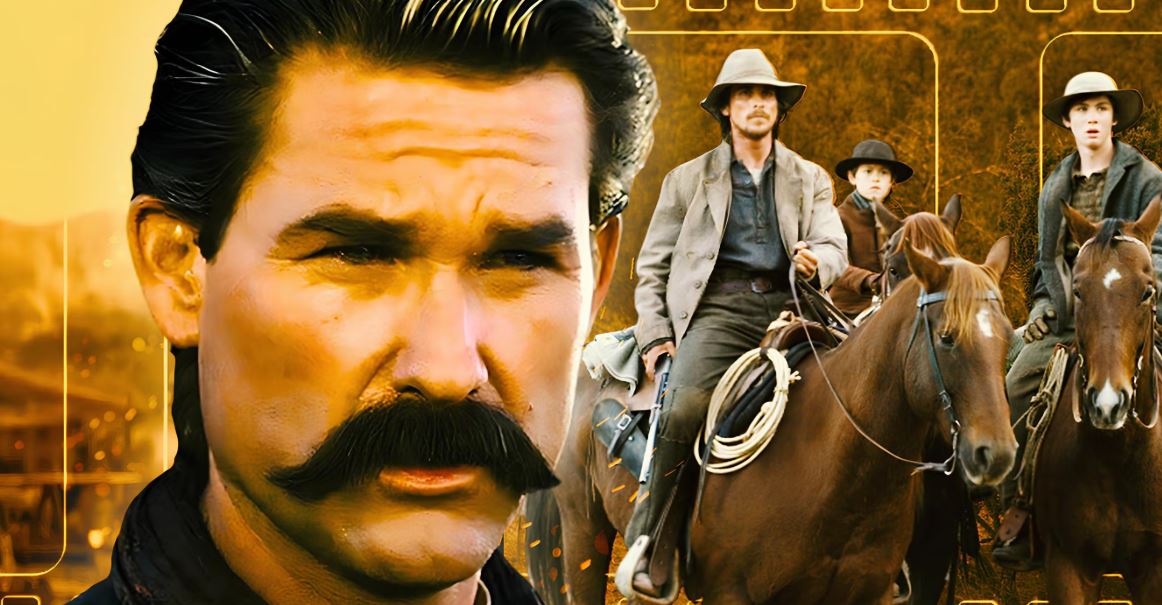

A showdown in the middle of a dusty “street” in a blossoming boomtown is the de facto emblem of the Western genre. No self-respecting cowboy film is complete without a gunfight, and George Cosmatos’ Tombstone is no exception. The ambitious two-hour classic is as genre-savvy as they come. Cosmatos and Russell’s joint dedication to the Western genre is emblazoned across the film’s face. It shines through in every wink and nod to an old classic. Every moment is drenched in authenticity and passion. Its crew endured some of the most demanding filming conditions, and they all performed beautifully.

It’s truly an all-encompassing love letter to the storied genre. But that doesn’t mean Tombstone is entirely clichéd. While it often leans into and even highlights its cultural and iconographic roots, Cosmatos’ film also has plenty of unique twists. Today, its ubiquity may make it seem mundane, but its final shootout is still a true masterpiece. More importantly, that gunfight turns the genre’s conventions upside-down. The posse battles the thick foliage of a lush forest to pursue their quarry. It’s nothing like the open streets and urban cobblestones found in most cowboy films. And it’s that imagery — the claustrophobic chase and in-built tension — that elevates the final conflict to epic heights.

The History of the Western Shootout

By most accounts, even the braved cowboys rarely saw the emblematic Wild West showdown. While a few hazy, sun-burnt carriageway face-offs may have taken place, few real gunslingers would agree to such ridiculously dangerous conditions. Really, it shouldn’t take much combat experience to realize a one-on-one duel with perfect visibility is a losing battle for both parties.

So, how did the iconic scene get its start? Duels weren’t everyday occurrences, but they still happened. Almost a century before the Wild West began its expansion, founding father Alexander Hamilton had his own (fatal) prototype showdown. The undeniably dramatic image of two men settling differences with bits of lead easily slipped into pop culture, and pulpy nineteenth-century dime novelists popularized a frontier version of the same scene.

While cinematic Western tales are built upon these romanticized conflicts, Tombstone pulls its story from a similarly esteemed historic pedigree. The film’s iconic downtown shoot-out is directly inspired by and often lovingly mimics the actual Gunfight at the O. K. Corral. (Although the actual event happened near, not at, the namesake establishment.) The now-iconic shootout gained its fame from Stuart Lake’s 1939 book, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Lawman.

By extension, many Western works pull from the same iconographic well. It’s a dramatic scene, after all. Urban gunfights remain a point of morbid fascination in modern culture. They present more opportunities for collateral damage and showcase the combatants’ marksmanship skills (or lack thereof). Such scenes also parallel daring stories of criminal escapades and dramatic bank robberies.

Aside from the cultural and historical basis of such conflicts, downtown face-offs come with plenty of narrative advantages. The villains can show off their immortality by using civilians as shields or abducting the hapless damsel in distress. The outlaws’ wanton disregard for property only emphasizes their law-breaking ways, as they usually seem downright gleeful to observe the resulting chaos. Just as art imitates life, art also uses life’s inherent perks to further its cause.

And the imagery is more than common. The dramatic downtown shootout is a pervasive, inescapable fixture in both classic and modern Western media. It’s been recreated countless times in innumerable films. The heart-pounding dangers of the situation are utilized and even encouraged in countless video games, particularly Rockstar’s Red Dead Redemption series. Even pinball machines, like Chicago Pinball’s Cactus Canyon, showcase reckless urban gunfights. And, of course, Tombstone’s climactic mid-film shootout is its own shining example of the trope.

Tombstone Places Its Final Showdown in a Different Setting Than Most Westerns

But the shootout in Tombstone, Arizona, isn’t the only gunfight in Cosmatos’ Western classic. It may be the titular conflict, but even the director acknowledges the epic showdown is merely the beginning of the film’s drama. Tombstone’s final fight happens at a lush riverside. There, the Earp posse faces down the ruthless Cowboys, not led by Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn), in a chaotic, fast-paced battle.

In some ways, the carefully choreographed scene plays out like a Vietnam War film. There’s little emphasis on brazen power and quick-acting trigger fingers. Wyatt Earp’s (Kurt Russell) quickdraw can’t help him. His gang drops to the ground and fires blindly. The resulting chaos is a dramatic showcase of gorgeous cinematography. It’s also a brilliant subversion of the genre’s typical landscapes.

The American West is more than a desert wasteland. Sparse shrubbery and towering cacti may dominate the Western genre’s imagery, but this iconography is yet another example of Hollywood shorthand. America’s landscape is filled with gorgeous, natural beauty. Even Arizona’s landscape is dotted with bits of greenery and grasslands.

On the one hand, the showdown’s setting cleverly separates it from the O. K. Corral fight. The practical delineation complements the scenery’s narrative importance. The thriving foliage contrasts with Doc Holliday’s (Val Kilmer) failing health. The river, meanwhile, is a dramatic spot for Earp to deal the final blow to “Curly Bill” Brocius (Powers Boothe). Note, too, that the setting’s inherent coverage adds an intriguing layer of suspense to the otherwise straightforward Western showdown.

It’s also worth noting that the events are historically accurate. Cosmatos and Russell could have reframed the final conflict as a more dramatic and conventional downtown shootout, but they stuck to the true story. Both Earp and the local paper, The Tombstone Epitaph, reported Brocius’ death in a riverside gunfight.

The forest finale of Tombstone is just one of many things that contribute to its massive legacy. Even now, decades after its premiere, Cosmatos and Russell’s masterpiece remains a beloved facet of Western media. Its visual and narrative brilliance still shine, and it remains an outstandingly entertaining movie. It’s everything a Western should be, but it still has a distinct identity.