Although “Heaven’s Gate” is now regarded in some circles as a misunderstood masterpiece, Michael Cimino’s lavish box office flop had a lot to answer for at the time. Not only was it blamed for the death of the American New Wave, but it was also seen as the final nail in the coffin of the Western. Released in 1980, the subsequent decade was an especially fallow period for the genre, but at least we got “Three Amigos.”

The drought lasted almost exactly 10 years until Kevin Costner’s “Dances With Wolves” became a massive box office success and went on to win seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director, reinvigorating the oldest and most resilient of U.S. genres once again. Two years after Costner’s triumph, Clint Eastwood’s harsh but lyrical “Unforgiven” was also a big hit with audiences and won the same big prizes at the Oscars. The Western was back.

These Revisionist hits renewed the commercial and critical success of the Western and paved the way for two new versions of the oft-told tale of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. One was Lawrence Kasdan’s sober biopic with Costner in the lead role, simply called “Wyatt Earp,” which was beaten to the punch and box office receipts by “Tombstone.”

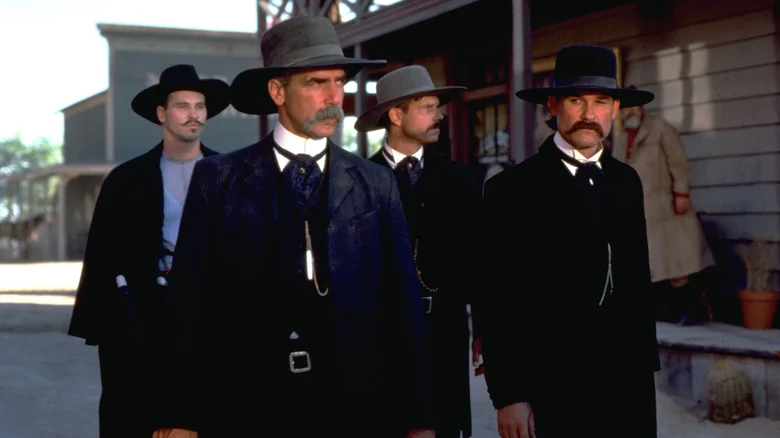

Directed by George P. Cosmatos, the man who brought us “Rambo: First Blood Part II,” the film became a popular modern Western classic, hitting the broad beats of true historical events while harking back to the crowd-pleasing elements of pre-Revisionist tales of the Old West. But does it sneak in some revisionism of its own among the magnificent mustaches and two-fisted action? Let’s take a look at some of its themes and how they all play out.

So what happens in Tombstone again?

“Tombstone” opens in 1879 with an outlaw gang known as the Cowboys, identified by their red sashes, riding into a Mexican town to avenge the deaths of two of their members. Led by “Curly Bill” Brocius (Powers Boothe) and his murderous right-hand man Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn), they gun down a wedding party and also kill a priest. Before he is shot dead, the preacher warns that they will face retribution from a sick horse, referring to the Fourth Horseman of the Apocalypse.

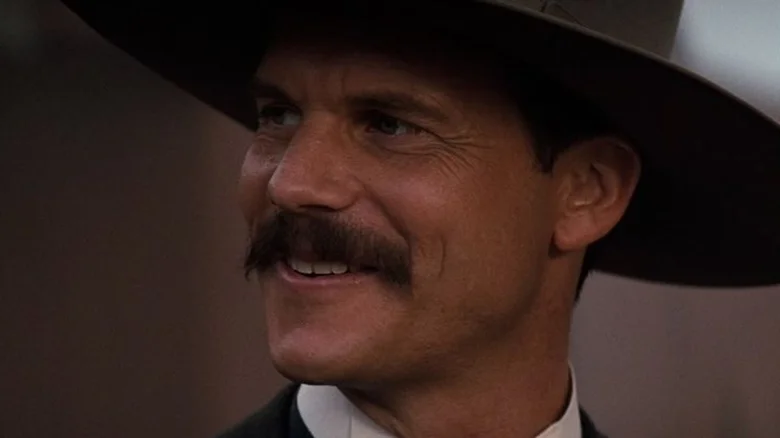

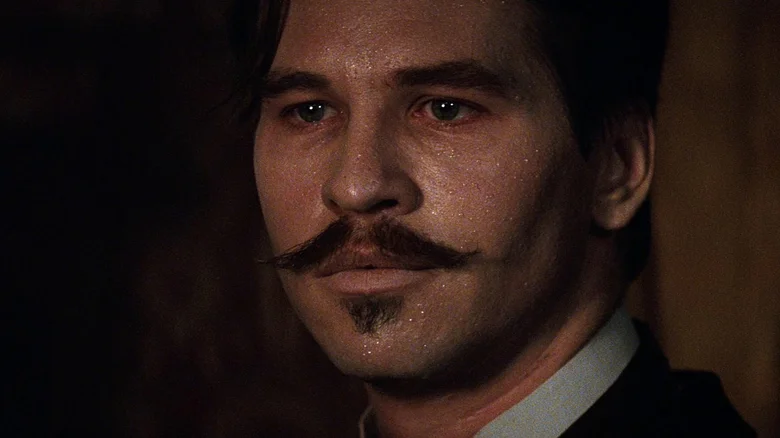

Meanwhile, retired Peace Officer Wyatt Earp (Kurt Russell) and his brothers Virgil (Sam Elliott) and Morgan (Bill Paxton) head to the Arizona boomtown Tombstone to settle down and make their fortune. Wyatt’s common-law wife Mattie (Dana Wheeler-Nicholson) is addicted to laudanum and his attention is caught by Josephine Marcus (Dana Delany), a traveling actor. Wyatt’s old friend Doc Holliday (Val Kilmer) also arrives in town, hoping the dry climate will ease the symptoms of tuberculosis.

Wyatt wastes no time throwing his weight around, humiliating a bullying saloon card dealer (Billy Bob Thornton) and taking over for a cut of the house’s winnings. Tombstone is depicted as a dangerous place, with law and order just about maintained by self-serving sheriff Johnny Behan (Jon Tenney), who delegates rather than getting his hands dirty.

Through a series of terse confrontations, tension rises between the Earp brothers and the Cowboys. After Curly Bill kills the town marshal, Virgil steps up to take his place and attempts to impose a ban on guns. Wyatt wants no part of it but, as the Cowboys return seeking a fight, he reluctantly backs his brothers. Joined by Holliday, they head out to disarm Ike Clanton (Stephen Lang), his brothers, and the McLaurys, resulting in a chaotic shootout outside the Old Kindersley corral.

Why is the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral so famous?

The legendary shootout only caught the public imagination once Stuart Lake published his biography “Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal,” two years after the former lawman’s death in 1929. He re-told the tale again 15 years later in his book “My Darling Clementine,” which provided the source material for John Ford’s celebrated western of the same name starring Henry Fonda.

Both books were fictionalized accounts and the casting of Fonda helped create the popular myth of Wyatt Earp as an upstanding character, although the true story was much murkier. The shootout itself wouldn’t become known by its popular name until John Sturges told the story again in 1957 in “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral,” with Burt Lancaster in the lead and Kirk Douglas as his famous sidekick, Doc Holliday.

John Ford claimed he had met Wyatt Earp on the sets of silent Westerns and that he had tried to emulate his version of the story. Ford’s tale illustrates how the end of the Old West bled over into the early days of cinema. The time of lawless frontier towns, heroic gunfighters, nefarious villains, and deadly shootouts may have become a thing of the past, but their legacy carried seamlessly onto celluloid. Edwin S. Porter’s “The Great Train Robbery,” released in 1903, is regarded as the first Western, and it was followed by dozens more in the silent era, making it one of the most popular early genres.

Other than “My Darling Clementine” and “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral,” there have been several other versions of the tale, further immortalizing Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday in Wild West lore. This brings us back to “Tombstone,” which at least tries to tell the full story of the deadly Earp-Holliday and Clanton-McLaury beef.

Tombstone also portrays the aftermath of the famous shootout

The notorious shootout only lasted around 30 seconds, which is perhaps why the romanticized “My Darling Clementine” and “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral” climaxed with the showdown. The violent confrontation of the real-life event, which left Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury dead, set the table for a bloody second act. The Earp brothers faced trial for the deaths of their opponents but the judge threw out the case; Virgil was ambushed and shot in the back and Morgan was killed in retaliation; and Wyatt set out to avenge his brother, killing four more of the Cowboys before eluding arrest by leaving Arizona.

“Tombstone” deserves credit for trying to tell the full story, but it suffers precisely because the gunfight is such an iconic event in Wild West lore. The build-up to the showdown is well-handled, establishing Tombstone as a raucous frontier town and cranking up the tension as hostility between the two factions grows. The film loses focus and suspense after the centerpiece gunfight, even though the screenplay ups the number of outlaws to stack the odds against Wyatt, Doc Holliday, and their posse. Indeed, Wyatt’s rampage is so committed that the Cowboys almost seem like the underdogs and Holliday’s final showdown with Ringo feels like a foregone conclusion after the preacher’s words in the opening scene.

There’s also something off about how Wyatt comes across in this movie. It’s no fault of Kurt Russell, whose heroic performance is at odds with a screenplay that casts Earp as a more shadowy figure than the romantic portrayals by Henry Fonda and Burt Lancaster. His pursuit of vengeance is uncomfortably vicious, summed up by the moment when an addled Cowboy mistakes the barrel of Wyatt’s gun for an opium pipe and gets his head shot off.

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and other biblical talk

Prefiguring Samuel L. Jackson’s “Ezekiel 25:17” speech in “Pulp Fiction,” writer Kevin Jarre clearly decided that biblical references were totally badass and stuffed his “Tombstone” screenplay full of them. They’re all pretty on the nose but, until the misjudged ending, it seems like they might serve some thematic purpose.

We begin with the preacher’s warning that a sick horse will come to get the baddies, referring to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. By the end of the film, Wyatt Earp’s posse is literally four horsemen with the sickly Doc Holliday, literally a Pale Rider, representing Death. In between, we get copious other references to hellfire, retribution, and damnation. Before things kick off, both factions attend a stage production of “Faust.” Johnny Ringo says he has already made his deal with the Devil; in that sense, he may be the most honest guy in the movie.

Other characters make choices that set them on course for personal hell. Mattie has surrendered to drug addiction and Doc Holliday won’t give up his hedonistic lifestyle, even though it is killing him; after a doctor’s visit, he accepts a cigarette from his lover and calls her the Anti-Christ. Morgan talks about how dying people see a heavenly light but, when he is bleeding in Wyatt’s arms, shot in revenge for the man he killed in the gunfight, he sees nothing. Has his guilt about taking a life condemned him to the fiery place instead?

Then we have Wyatt. Early on, he says he has a guilty conscience because he once killed a man. By the end, he has killed many more. “You tell ’em I’m coming! And Hell’s coming with me!” he roars before pursuing vengeance with a sadistic glee that makes him seem hellbound. This brings us to the film’s biggest flaw.

Tombstone botches the revenge aspect of the story

“Tombstone” isn’t generally regarded as a Revisionist Western, but it ends up pitching somewhere between white hats versus black hats myth-making and a revisionist take on the familiar story. Revisionist Westerns often deglamorize the violence associated with the genre and portray gunslingers as relics of a brutal era, as we see in “The Searchers,” “The Wild Bunch,” and “Unforgiven” (the latter of which released the year before “Tombstone”).

Kevin Jarre’s screenplay staggers wildly like a drunken cowboy leaving a saloon on this point, and it’s worth comparing with Clint Eastwood’s film to highlight why. Eastwood plays Will Munny, a retired outlaw haunted by his past deeds. In need of cash, he takes a gig that is notionally honorable, hunting down two cowboys who evaded justice for cutting up a sex worker thanks to a corrupt sheriff. Nevertheless, when Munny finally unleashes his violent side in a bloody conclusion, there is nothing honorable about it at all.

Broadly following events after the gunfight, “Tombstone” becomes a revenge narrative. Revenge thrillers often, if not always, suggest the protagonist corrupts their own soul by pursuing bloody retribution. Wyatt Earp’s ruthless killing of the Cowboys indicates that he has become almost as bad as the outlaws, but the film bungles the point. Furthermore, Bruce Broughton’s conventionally rousing score urges us to cheer him on instead of questioning his actions.

Even more confusingly, the film rewards Wyatt with an undeserved happy ending as he dances blissfully in the snow with Josephine. Almost as an afterthought, Robert Mitchum’s narration mentions that Mattie, the tragic woman Earp dumps for his new lover, died a few years later. This forced romantic conclusion sits at odds with the sadistic carnage of the Cowboy hunt, leaving a sour taste and the impression that the filmmakers didn’t know what point they were trying to make.

Tombstone’s stake for a place in western history

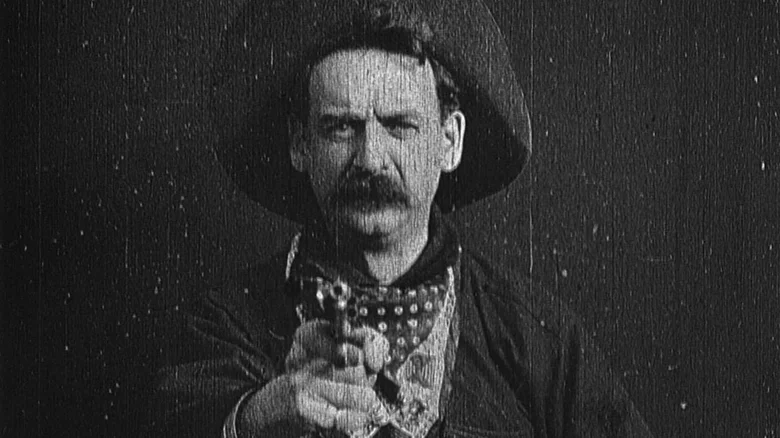

“Tombstone” never ceases to remind us that it is part of a long cinematic tradition of Western movies, bullishly staking a claim for its place in the history of the genre with its silent-era prologue. In this sequence, we get the modern actors in scratchy black and white, mocked up to look like ancient footage from the turn of the 20th Century. To complete the connection, the montage ends with the famous shot of a cowboy firing directly at the camera from “The Great Train Robbery.”

Robert Mitchum appeared in 29 Westerns over his long career, and his voice-over is another nod to the genre’s heritage, as is Charlton Heston’s distracting cameo. He also starred in several Westerns of the classic Hollywood period.

This pitch at Western relevance is an interesting take on another preoccupation of Revisionist Westerns: How the Old West gave way to modernity. Usually, this is represented by cars replacing horses as a mode of transport or modern weapons supplanting the classic six-shooter, as brutally demonstrated at the end of “The Wild Bunch.”

After his storied career, the gunfight at the O.K. Corral, and later adventures, Wyatt Earp settled in Los Angeles and served as a consultant in the new-fangled medium of motion pictures. By the time he passed away in 1929, cinema had taken its next evolutionary leap into the Talkies and a future icon named John Wayne was a year from appearing in his first Western.

In his closing narration, Robert Mitchum tells us that William S. Hart and Tom Mix, two early Western stars who became friends with Earp, acted as pallbearers at Earp’s funeral. This footnote is a poignant reminder that while the Wild West has long since passed into legend, legend has passed into cinema and lives on in movies like “Tombstone.”