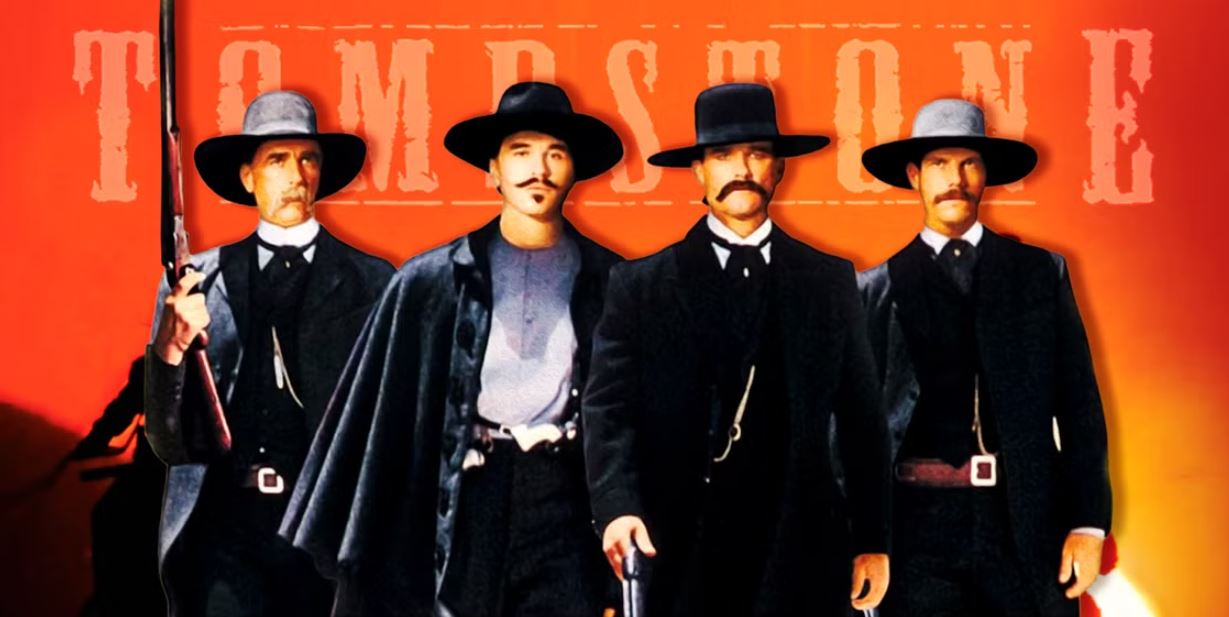

It’s hard to imagine the modern Western genre without George Cosmatos’ Tombstone. At this point, the Arizona-set masterpiece has surpassed the status of an everyday film. It’s wormed its way into the cultural zeitgeist. Its greatest quotes and moments have become cultural shorthand for the Wild West. Of course, part of that success is driven by the film’s innate spectacle. Despite a relatively brief runtime, Tombstone packs a massive punch. It’s a three-course auditory, narrative, and visual feast.

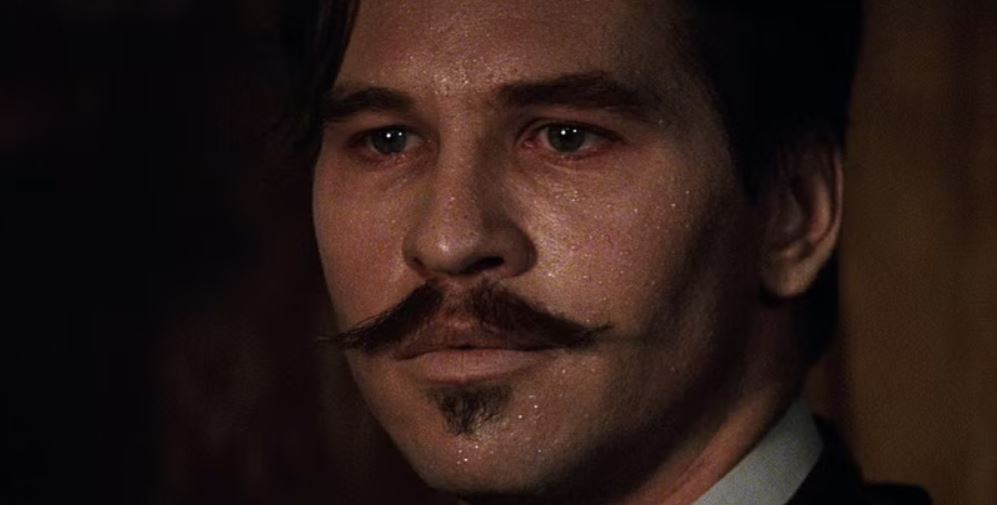

Few things appear without a good reason. The same can be said of the plot. While some of the film’s “downtime” may seem like unnecessary patter, even the smallest moments have a huge impact. One such “throwaway” scene seems like little more than a scene transition. The camera deftly pans across the stiflingly hot interior of a saloon. It passes revelers and offers a brief glimpse of a balding bartender. Off-tune piano music floats through the air. Eventually, as the motion stops, the audience realizes the pianist is none other than Doc Holliday (Val Kilmer).

George Cosmatos’ Tombstone Consistently Pays Homage

- Despite Tombstone’s success, it is only the 16th most profitable Western released since 1979.

- The film’s complete soundtrack, featuring Bruce Broughton’s sweeping score, was not released until 2006.

- Tombstone was not Broughton’s first Western score. He also worked on Gunsmoke, The Oregon Trail, and How the West Was Won.

It’s just one of Tombstone’s many tiny, intricate details. Cosmatos and Russell’s joint vision is a true masterpiece of the genre. The film’s heart-pounding shootouts epitomize the grit and tenacity of Western cinema. At the same time, its slower moments perfectly capture the dust-streaked mythos that permeates the genre.

One could argue that Tombstone can also qualify as a historical drama. Despite its Western branding, the film teems with obsessive detailing. The flickering light of saloon candles casts shadows across time-worn wooden furniture. Towering trees envelop a life-or-death shootout, creating a living time capsule. From the moment it begins, Cosmatos and Russell’s film is a cinematic time machine. Tombstone deftly reels audiences into the past and throws them into the burning sun. Yes, it sings the romanticized praises of a divisive and often brutal period. But it does so with a sense of awe and reverence.

It goes beyond the surface-level set dressing of many modern Westerns and recalls the golden era of gunslinging cowboys. Both Cosmatos and Russell were known on-set for their historical accuracy. The prop department acquired as many authentic pieces as it could. What could not be purchased was manufactured for the film.

Interiors were lit by candlelight and lacked the air-conditioned modernity that makes desert life more bearable. Every actor was clad in heavy wool clothing and leather hats. They labored for hours beneath the suffocating heat of Arizona to create an inimitable modern masterpiece. Their work paid off, but it certainly didn’t come without a literal and physical connection to the past.

And the film’s details don’t stop there. Tiny glimpses of the future are scattered throughout Tombstone. In its opening, Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn) listens to and translates a Spanish church service. Its words, which detail the “pale horse” of death, serve as a spine-chilling prelude to the film’s violence.

Doc Holliday and the Significance of a Piano

- Kilmer was controversially snubbed at the 1993 Oscar Awards.

- Kurt Russell stepped back from his role to support the film’s directorial staff.

- Most of Tombstone was shot on location in Arizona.

But that homily is an obvious instance of foreshadowing. Holliday’s piano playing is more subtle. After scratching the surface, it’s easy to see the scene as a showcase of Holliday’s intellect. Despite his role as a gunslinger, Doc Holliday was still a well-educated man. His nickname was no exaggeration; when he wasn’t gambling, he was a respected and talented dentist. Like many men of the era, he was raised on the East Coast and left to find fortune.

Historically speaking, playing piano was just one of his many talents. As Kilmer so expertly portrays, Holliday was also an avid reader and skilled rhetorician. While he certainly had his fair share of fights, his larger-than-life reputation also came from a sense of natural showmanship and self-promotion. He was also a polyglot, capable of speaking English, French, and Latin.

Considering that, it’s easy to see the piano tune as another brilliant display of talent. But it’s worth a second look. This brief snippet of music is very specific. Kilmer, who learned how to play the song for his role, is playing an off-key rendition of Frédéric Chopin’s “Nocturne.” It’s a seemingly strange inclusion in a cowboy movie, but the peaceful tune, first published in 1834, would have been known to Holliday.

As the composition’s title suggests, Chopin’s piece is one of the world’s many nocturnes. Historically, such songs were played at parties as light entertainment. These character pieces are inspired by the silence and peacefulness of nighttime, a stark contrast to Holliday’s ruthless demeanor throughout Tombstone. Of course, nighttime also symbolizes the end of the day — and, by extension, life.

And the song choice goes even deeper. Like Holliday, Chopin met an early demise. While the cause of death has been debated for decades, a 2017 report by the American Journal of Medicine added another layer of retrospective brilliance to the song’s inclusion. After extensive study of Chopin’s medical records, doctors concluded the esteemed composer died of tuberculosis, the same disease that claimed Doc Holliday’s life.