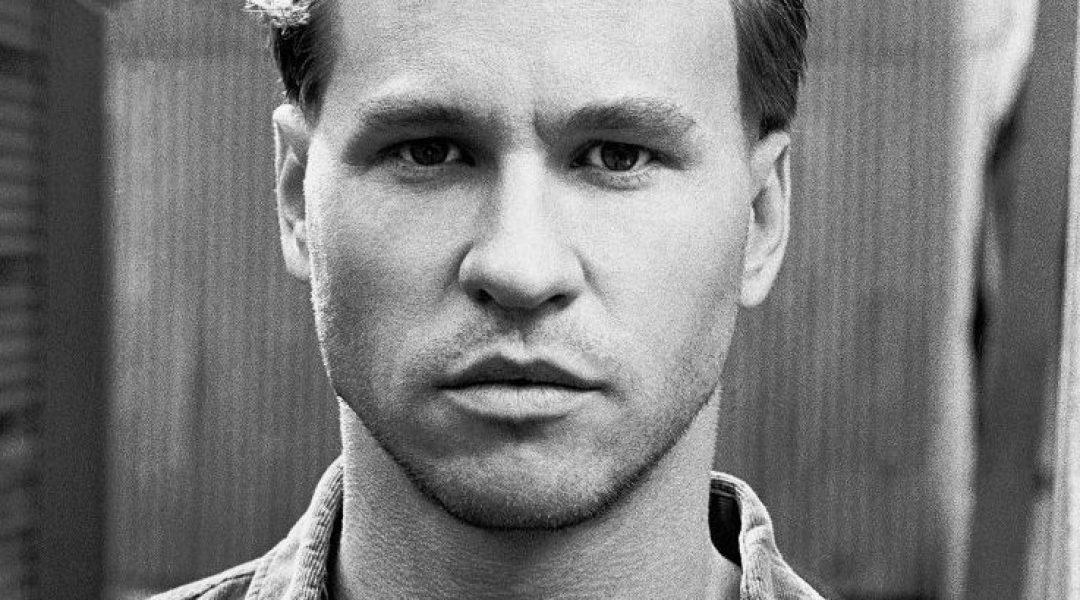

The new biographical/autobiographical film about Val Kilmer was saved to my Amazon Prime Video watchlist along with dozens of other shows I’d get to eventually. But when I saw a photo of a very young, impossibly handsome Kilmer in a straw cowboy hat in a Collider review of the “documentary,” I decided to watch it that very moment. Not for the handsomeness — that was old news. For the cowboy hat. What was he doing in that?

Turns out Val Kilmer is a man who wears many hats. And he’s a man with many faces and passions. Val acquaints you with a lot of them.

It goes without saying — and Val is a potent reminder — that you never know people based on your own finite, flawed human observations, especially famous people you only think you know from all the media coverage you’ve soaked up. I certainly didn’t know Val Kilmer. Now, having spent one hour and 48 minutes with him, I feel I know — and understand — something. Maybe a lot.

Whether or not the film accurately depicts the story of Val Kilmer is up for debate. How could it tell the whole of his 61 years? But while it might not be a complete and fully objective 360 of his life, it’s got the arc and lots of compelling footage.

Turns out Val Kilmer is a man who wears many hats. And he’s a man with many faces and passions. Val acquaints you with a lot of them.

An esteemed colleague sent me a smart Variety article questioning the genre of the film: Was it a documentary or something else? If the subject himself has a lot of creative control and the story isn’t exactly a balanced examination of a life, what do you call that?

I’m not sure. It’s a good question and probably a necessary one as more and more collaborative/vanity projects blur the lines of pure documentary. What I can answer is whether I was entertained by Val. Yes. Did I learn stuff about Kilmer that I found revelatory? Yes. Was there an element that transcended the story of one man to inform more broadly about the human condition? Yes.

Would I recommend it? Yes.

You, like me, might not even realize you have opinions about Val Kilmer beyond the movies you’ve seen — his portrayals of Iceman (Top Gun), Jim Morrison (The Doors), Doc Holliday (Tombstone), and Batman (Batman Forever). If you’ve been following him more closely, there’s his acclaimed turn as William Bonney in Gore Vidal’s Billy the Kid, his portrayal of FBI agent Ray Levoi in the neo-western Thunderheart, and his relatively recent take on Mark Twain (Citizen Twain, Cinema Twain). That’s just some of his body of work.

You, like me, might not have considered him much beyond his movies, his reputation for being difficult (that whole The Island of Dr. Moreau thing), his ladies man résumé (Cher, Ellen Barkin, Angelina Jolie, Darryl Hannah, Carly Simon, Cindy Crawford, Michelle Pfeiffer, among others), and his battle with throat cancer (the reason he can no longer speak without placing a finger over the permanent voice-box hole in his neck).

Val Kilmer is a lot to take in. Luckily there’s tons of film capturing him in his early days and onward — including home movies and amateur film projects made with his kid brother, Wesley — from which you can try to devine who he might be off screen and off stage.

Kilmer got the film bug early and started carrying a camera seemingly everywhere all the time. Did he just love storytelling? Was he terribly vain? Both? Maybe it doesn’t matter. He’s got it on film, he warehoused all of it, and he, along with filmmakers Ting Poo and Leo Scott, makes good use of it in Val.

“He was onto the whole obsession with self-recording ahead of everyone else; he kept a video camera running at home, on movie sets, wherever he was,” Owen Gleibeman writes in Variety. “What makes Val a good and heartfelt movie, rather than just some glorified movie-star-as-trashed-parody-of-himself piece of reality-show exploitation, is that Kilmer brings the film an incredible sense of self-awareness.”

You are left to connect the dots however you like, but the plot points are pretty indelible — many poignant. You feel like you understand, maybe along with Kilmer himself, for instance, that if he’s been an insufferable asshole at times in his life, it might have something to do with losing his brother Wesley, who died at age 15 by drowning in the family Jacuzzi during an epileptic seizure. The tragedy clearly colors Kilmer’s life with a soul-deepening sorrow that would have had to manifest somehow, and often, and crops up in Val several times.

Val Kilmer is a lot to take in. Luckily there’s tons of film capturing him in his early days and onward…

The Kilmer kids grew up in “the Valley” — on the San Fernando ranch once owned by Roy Rogers and purchased in Val’s youth by his dad. As the Los Angeles Times once explained, businessman and real estate developer Eugene Kilmer bought the ranch at the top of Trigger Street in 1969 (when Val would have been about 10); the place included a 6,000-square-foot ranch house with six bedrooms and six bathrooms, a guest house, tennis court, pool, and spa on three and a half acres of land, along with an additional 100 undeveloped acres.

Roy Rogers and Dale Evans had been happy on what was then their 300 acres, the Los Angeles Times reported, but after “they lost a child in a bus accident on a church outing — their third child to die — the couple sold the property, saying it held too many sad memories for them.”

You sense something less like sadness and more like revulsion when Kilmer returns to the area in the film. Whatever his one-time California home might have meant to him and whatever happy memories it might have once held, this is where his brother died and where his father came to financial ruin (Kilmer bailed him out). He seems to physically recoil as he drives around the now-developed area remembering what it used to be and surveying what it has become.

Kilmer would eventually own his own ranch — his was a beloved spread in New Mexico outside of Santa Fe — and you see him riding there, skinny-dipping in the river that ran through it, cradling a newborn on his chest in the old adobe house he shared with his wife, British actress Joanne Whalley. He raised his kids there, and you get to see the cool adults they’ve become. Son Jack narrates the film and sidekicks around with his dad throughout. Devoted daughter Mercedes appears too and seems to be a duplex-mate living next-door now that Kilmer no longer owns the New Mexico ranch, apparently having had to sell it to pay off debts post-divorce.

His faith (passed on to him by his devout mother, a sort of emotionally reserved Christ Science Swede and showy wearer of Native jewelry). His painting (a whole series that uses “GOD” to visual and spiritual effect). His style (layers of silver and chunky turquoise necklaces and cuffs and scarves that dashingly disguise the trach hole). His devotion to his craft and his fans (preparing for heady parts early on, of late gratefully “headlining” minor events very far from the red carpet).

His physical struggles (having to vomit and being whisked away in a wheelchair with a blanket over his head to lie down midway through an autograph session at some movie convention only to return later to resume graciously signing his name on all manner of memorabilia). His practical joking and wisecracking (including spraying his scolding ex with Silly String on the way to his mother’s funeral in Wickenburg, Arizona). There’s so much here that’s moving and meaningful.

Sure, there’s stuff like pre-fame Kevin Bacon and Sean Penn mooning the camera for Val, as Kilmer was just starting to make his way in the world after studying drama at Juilliard. But the most affecting aspects of the film don’t have to do with titillating things about famous people. Rather, they have to do with Kilmer’s deeply personal, even confessional and haunting, ruminations on his family and faith, films and fame.

Why did it come as a surprise that he’s articulate in giving voice to his own very human drama? Because he’s blond and good-looking?

He has quipped that playing Mark Twain was tough because it’s “a bitch” to play “a genius,” and Kilmer claims not to consider himself in the category. I don’t know about that. He reads a little poem to an audience early in his career that is short and sharp, insightful and funny. If he weren’t deep and multifaceted, Val might have been yet another title in your streaming queue you’d enjoy then move on from and forget.

But it stays with you, days on. As does the man.

Some parts of the film especially take hold and won’t let go. When Kilmer talks about Tombstone, the emotion resonates. He thinks of it as a love story between his Doc Holliday and Kurt Russell’s Wyatt Earp — like some cosmic inverse of his arrogant, competitive, chest-inflating airman competition with Tom Cruise. The clip of Doc’s deathbed leave-taking from Wyatt is heartbreaking, not just for the moment in the movie but also for the near-death experiences Kilmer has endured in the meantime — and all the more when he reveals that in striving to adequately express the dying Holliday’s pain he arranged to lie on a bed of ice for the scene. When you watch it again, the scene conveys even more suffering.

Scenes like that, stories like Kilmer’s, beg the question: When your looks and health are taken away, what is the measure of the man that remains?

Maybe Kilmer’s affinity for Mark Twain hints at an answer. Maybe his borderline obsession — from which proceeded his one-man stage show Citizen Twain and the 2019 film version, Cinema Twain — has something to do with shared tragedy and the use of humor to blunt the pain. Twain had a son who died at 19 months (diphtheria) and a daughter who died at 24 (spinal meningitis). Shortly before Twain’s own death, his youngest, daughter Jean, died by drowning in a bathtub at home at age 29 after having an epileptic seizure; Kilmer lost his brother Wesley in a similar tragedy when they were both just teenagers with their lives ahead of them.

By those kinds of devastating fires we are finally purified or ultimately destroyed. Kilmer has survived and seems on a path of some kind of purification.

Scenes like that, stories like Kilmer’s, beg the question: When your looks and health are taken away, what is the measure of the man that remains?

He has said in interviews that he’s been working on not being vain. Would that more movie stars put in that work to earn their places on our collective dais. It’s perhaps facile to presume that aging, cancer, and the cumulative effect of life’s trials and tribulations have helped Kilmer plumb his own depths for reasons beyond self-adulation. If this film was just an exercise in vanity, I was totally fooled and taken in.

If there are vestiges of vanity, well, it’s a lifelong effort to stomp out that strong weakness, and probably a lot harder for people in the ego-stroking spotlight. But in the film and the man, I saw and was touched by something redemptive: a need for acceptance, forgiveness, comfort, love, understanding.

In Val, Kilmer might be curating his legacy before someone else does less favorably. But even if that’s the case, Val is indeed a good and heartfelt movie.

Maybe I missed the whole point. Maybe I’m reading too much into it. Or maybe I just fell stupidly hard for the handsome, hot guy in the beat-up cowboy hat. But more than a week after watching Val I’m still thinking about it — and him — like I met another switchbacking pilgrim on the hard climb to the final destination and feeling thankful for the thoughtful, interesting company.