There is no more precarious moment in a movie star’s career than the day they wake up, flush with box office success, and declare, “What I’d really like to do is direct!” Slightly less dangerous is a star’s inclination to produce –- i.e., to diversify their career by generating material that reflects their taste or broadens their brand.

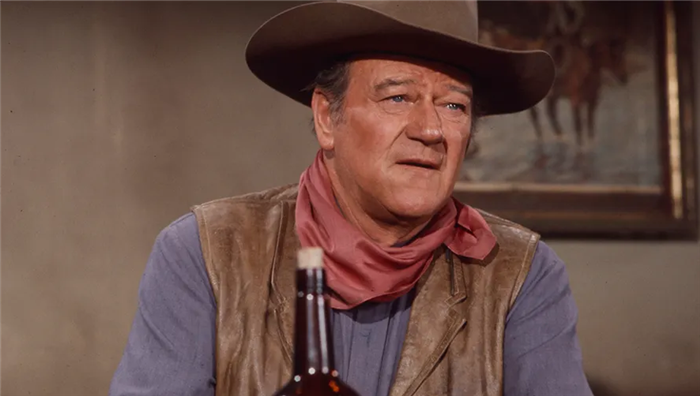

Two years after the end of World War II, John Wayne, who’d sat out the civilization-saving conflict while colleagues like James Stewart and Henry Fonda served, realized he was the biggest star in Hollywood and ought to start calling his own shots. Rather than direct, he found a quaint Western called “Angel and the Badman” written by James Edward Grant, in which a Quaker woman nurses a wounded gunfighter back to health.

For an actor who’d made his name as a kickass, take-charge hero in Westerns and war movies, this was an oddly anti-violent movie. Nevertheless, Grant’s story connected with The Duke, and it became the first film to bear the credit of “A John Wayne Production.” Being the man in charge for the first time in his career taught Wayne a number of lessons.

The Duke becomes The Boss

As Wayne’s stature grew in the industry, he developed certain expectations around the way sets should be run. According to Scott Eyman’s “John Wayne: The Life and Legend,” when he became a producer, he made sure his collaborators understood that he demanded a certain level of commitment.

“I used to be a little vague about when I reported to the studio mornings,” he said. “But now I’m ahead of time. I know all my lines. I love all the other actors in the troupe who don’t blow lines.”

Granted, this is the bare minimum one should expect from their on-camera employees, but Hollywood has always been rife with talented performers who get away with a lack of preparation because, in the studio’s view, they’re ultimately worth the trouble.

The most fascinating aspect of “Angel and the Badman” was Wayne’s belief in a film wherein his gunfighter lays down his weapons during the obligatory showdown. The final line of the movie is delivered by Harry Carey’s Marshal Wistful McClintock: “Only a man who carries a gun ever needs one.”

John Wayne: Pacifist

If the plot sounds familiar, that’s because it pretty clearly inspired Peter Weir’s masterful “Witness,” in which Harrison Ford’s streetwise Philadelphia detective is rehabilitated physically and spiritually in an Amish community. When asked about his choice of material, Wayne was careful to let “Angel and the Badman” speak for itself:

“I think we’ve got a swell story –- I found it myself. I even think it’s got a message. Anyhow, it’s one I wanted to do. James Edward Grant wrote it, and the only way he’d sell it to me was for me to give him the chance to direct it. So I did. As a producer, I want to give new people chances. If they click, I’ll feel that it will be a sort of repayment for the brand of friendship and trust that [John] Ford has given me.”

Wayne would eventually form Batjac Entertainment, which turned out two excellent films in Budd Boetticher’s “Seven Men from Now” and Frank Borzage’s “China Doll.” Ever the image-conscious star, Wayne made plenty of red-blooded, patriotic films to satiate his mostly conservative fan base, but the fact that he kicked off his producing career with the pacifistic “Angel and the Badman” says something about the man’s soul.