Not too long ago, the actor Sam Elliott, who has spent much of his 46-year career alternately fighting and embracing habitual typecasting as America’s cowboy, was referred to as a “male ingénue.”

At 79, Mr. Elliott is not young, and anyone who’s witnessed the knowing gleam in his peepers wouldn’t for a second peg him as innocent. But with lauded performances this year in three indie films and guest spots in two acclaimed television series, Mr. Elliott is definitely having a moment.

In May, he was named best guest performer in a drama series at the Critics’ Choice Television Awards for his work on FX’s “Justified.” The film “I’ll See You in My Dreams,” in which he played a leading man for the first time in years, opposite Blythe Danner, steadily drew crowds despite its limited release this spring. (It was a co-star of that film, Mary Kay Place, who slyly called Mr. Elliott an ingénue.) He appeared in another Sundance indie, “Digging for Fire,” and in February returned to “Parks and Recreation” to play the vegan hippie Ron Dunn.

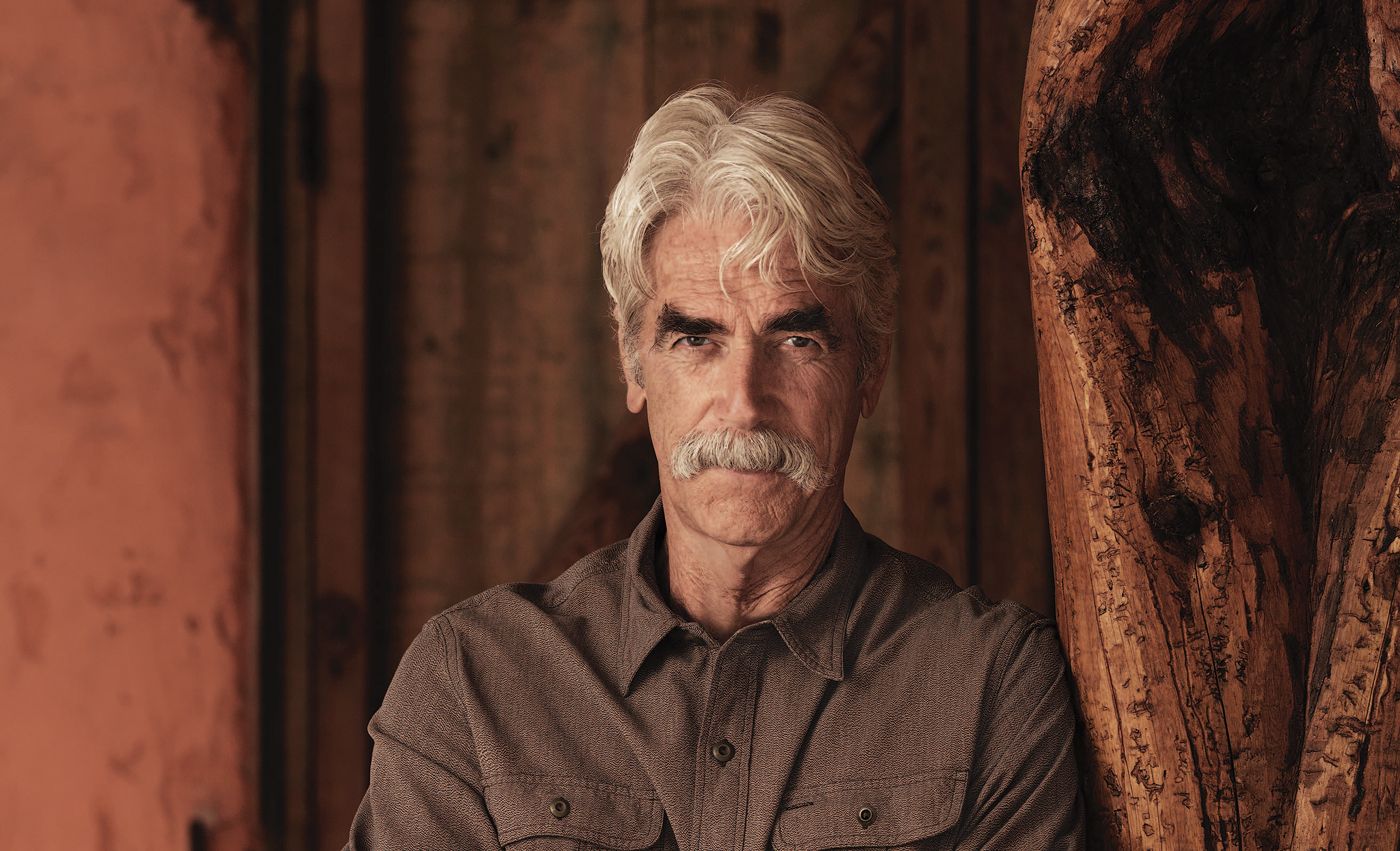

But it is Mr. Elliott’s turn as a spurned lover in “Grandma,” which stars Lily Tomlin and opens Aug. 21, that has garnered him some of his warmest reviews yet: He brought a ferocious emotional rawness to the part that caught critics and even the director off-guard. Variety’s Scott Foundas raved that Mr. Elliott had, in 10 minutes on screen, created “a fuller, richer character than most actors do given two hours.” The Awards Circuit website said he should be considered for an Oscar.

“What he does in that moment in some ways became the emotional core of the film,” said Paul Weitz, who wrote and directed “Grandma.” “You’re not used to the idea that this person is going to expose himself as an actor.”

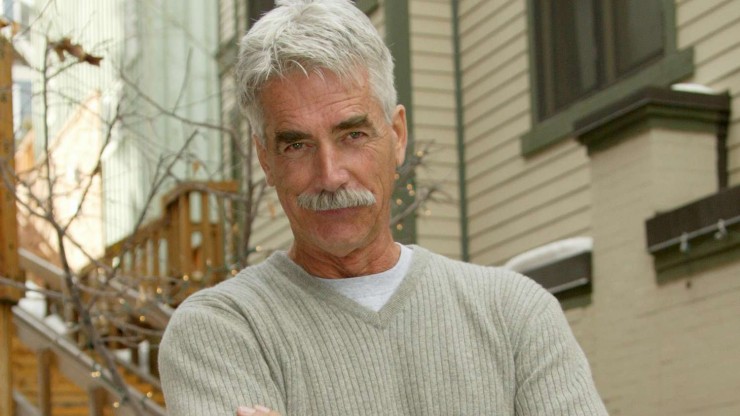

Indeed, Mr. Elliott’s resonant baritone growl, which still weakens the knees of female fans, and mustache, rendered in multiple shades of handlebar, have, over the decades, become synonymous with stoic, steely dudes: usually cowboys (“Tombstone,” “The Big Lebowski,” “The Golden Compass”), followed by bikers (“Roadhouse,” “Mask”), pilots (“Up in the Air”) and military men (“Hulk,” “We Were Soldiers”). That Mr. Elliott has been able to remain, as a septuagenarian, the man many guys want to be and gals want to be with is also a testament to his sustained, indisputable, silver foxiness. Commenting on a video of him speaking in January at Sundance, one fan wrote, “This man must be at least 87 percent testosterone.”

In “Grandma,” Mr. Elliott said, he was able to stretch beyond the narrowed bandwidth that comes with playing an idealized type of man. This break from character, he said, brought a measure of unforeseen relief. “I came unglued a little bit, and it happened in the doing of it,” he said, or, rather, drawled. “It was a real catharsis, in a positive way.”

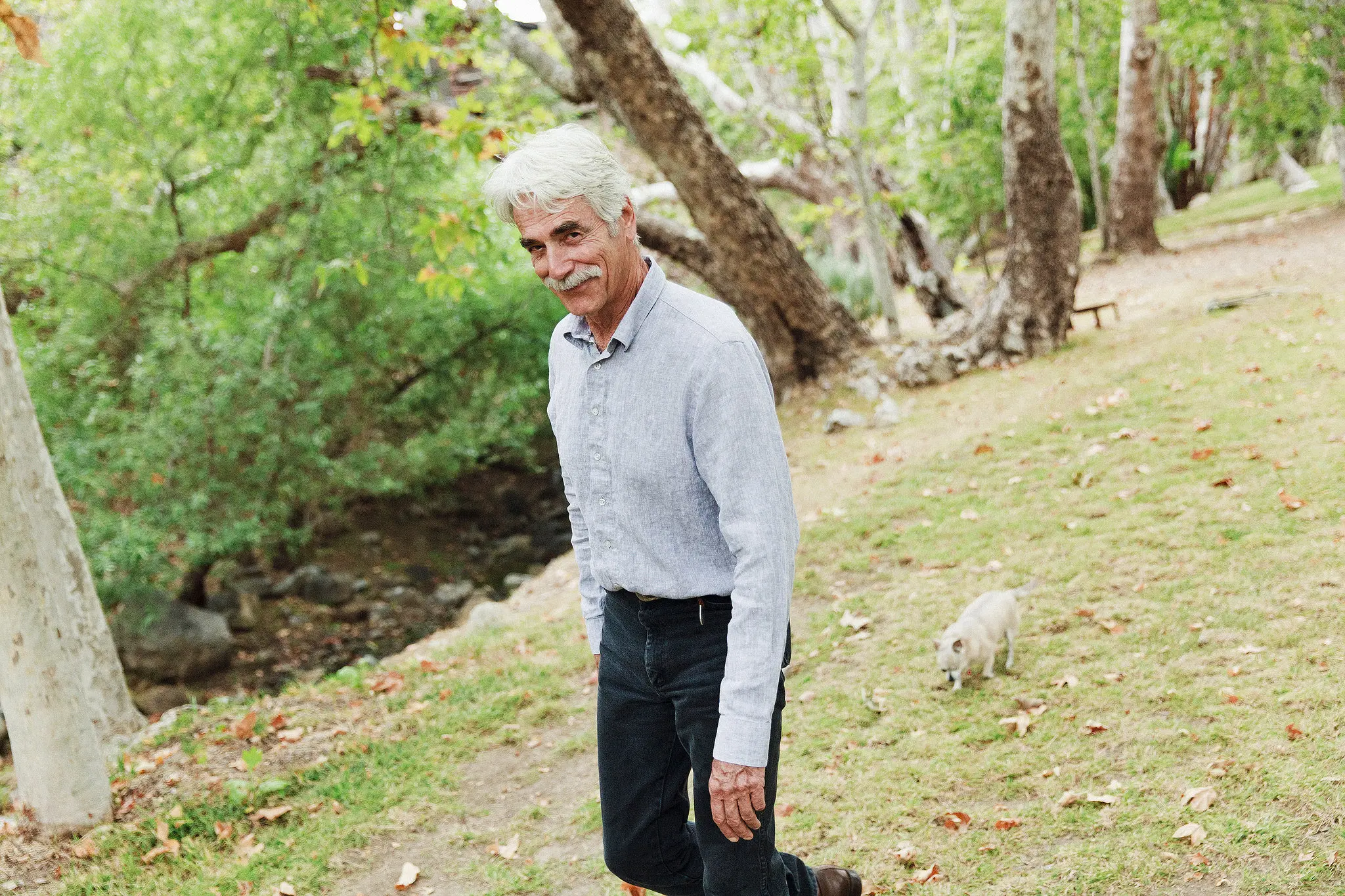

Mr. Elliott was speaking in his rambling, Southwestern-style seaside home, as one of his dogs, Dionne, aged and ailing, lay sighing at his feet. Mr. Elliott and his wife, the actress Katharine Ross (enduringly known as the bride in “The Graduate”), have been living on their three acres here for some 40 years, first in a house that burned to the ground in a brush fire, then in a double-wide trailer, and finally in this home, set amid an Edenic thicket of flowering trees. They used to stable horses on the property, but now just keep chickens, along with Dionne and a waddling, one-eyed Chihuahua named Marina.

The couple, who have a daughter, Cleo, 30, are toying with moving to Oregon, where Mr. Elliott spent his adolescence after an early childhood in Sacramento. But work has been coming at such a quick clip that he hasn’t yet had the chance to clean out his mother’s house there since her death three years ago. And while images of Mr. Elliott in a 10-galloner may be indelible, none of the recent parts have been in westerns.

It is hard to pinpoint when exactly Mr. Elliott became fixed in popular imaginings as Hollywood’s prototypical cowboy, but for Mr. Elliott it became starkly apparent in the late ’90s, when he was approached for “The Big Lebowski.” By that time, roughly a quarter of all the parts Mr. Elliott had landed were in westerns, a number that was growing, and he was eager to switch things up.

Then he was given Joel and Ethan Coen’s screenplay.

“We hear male voices gently singing ‘Tumbling Tumbleweeds,’ ” it begins, “and a deep, affable, Western-accented voice — Sam Elliott’s, perhaps.” The voice belongs to the Stranger, later described as “middle-aged, amiable, craggily handsome — Sam Elliott, perhaps. He has a large Western-style mustache and wears denims, a yoked shirt and a cowboy hat.”

Mr. Elliott recalled thinking: “ ‘Even in a Coen brothers movie, I can’t play one of their wacky characters, I gotta play a cowboy.’ I think you feel, on some level, when you get boxed in in this business, you get sold short.”

Mr. Elliott ended up loving to work with the Coens, and the admiration was mutual. After shooting the last scene perhaps 15 times, Mr. Elliott finally said, “Guys, you’ve got to tell me what you want.” They replied, he recalled, that they had gotten what they wanted on the sixth take, but just loved watching him do it over and over again.

Since then, Mr. Elliott said, his resistance to playing cowboys has softened to gratitude. Appearing in “The Big Lebowski,” which starred Jeff Bridges as the Dude, helped get him a key role in “The Contender” (2000), playing a close adviser to Mr. Bridges’s president. Mr. Elliott said the director, Rod Lurie, told him, “I just want to see more of you and the Dude.” Mr. Elliott’s casting in Chris Weitz’s “The Golden Compass,” again as a cowboy, eventually led to the role in “Grandma”: Chris and Paul Weitz are brothers.

“I used to grouse about it, until I grew up a little bit,” Mr. Elliott said of the typecasting. “I really realized it was nothing but good fortune to be in any kind of a box in this business. You know what I mean?”

Tall, slim and as toothsome as ever, he still fits the part. In a cinematic landscape riddled with man-boys and testosteronic action men, Mr. Elliott exudes effortless gentlemanliness and old-fashioned assuredness and calm, none of which is lost on his legions of dogged fans.

In May, Mr. Elliott attended a packed screening of “I’ll See You in My Dreams” at an AARP convention in Miami. Afterward, during a question-and-answer period that included Brett Haley, the film’s writer and director, Mr. Elliott was greeted with roars, as women in their 60s, 70s and beyond conveyed, in quavering voices, their undying love. Others got on their knees, trying to get as close as possible to where he sat onstage. “I’ve never been to a One Direction concert,” Mr. Haley said, “but that’s what it felt like.”

Mr. Haley is among several younger male directors who have worked with Mr. Elliott and been left in a state of something close to awe: He described his leading man as “extremely sensitive and insightful; kind and generous and very smart.” Paul Weitz called him “one of the most gentlemanly, kind people I’ve come across.” Peter Sohn, who directed Pixar’s coming “The Good Dinosaur,” for which Mr. Elliott voiced a Tyrannosaurus named Butch, said Mr. Elliott was jaw-droppingly perfect in the role and heartwarmingly sincere. “I realize I’m gushing,” Mr. Sohn said.

Each had stories of Mr. Elliott’s decency on the set. Of his refusing to let anyone fetch him a drink. Of his showing up in his pickup truck so early for work that Mr. Weitz initially mistook him for an especially eager crew member. Of his readily agreeing to go with Mr. Haley to a retirement community to thank its residents for letting them film there. “He said: ‘That’s a good thing you’re doing. I’ll be there,’ ” Mr. Haley recalled. “He took pictures with people for hours and hours.”

Second nature, Mr. Elliott said. “Gentlemanliness comes natural to me. That’s the way I was raised,” he said. “That’s part of the deal.”

Mr. Elliott always knew he wanted to act, and after singing in cherub choirs and appearing in small theater productions and musicals — “My voice became bass very early on,” he said — he moved back to California at age 20. He was one of the last actors signed under the studio system, becoming a contract actor at 20th Century Fox, before appearing in a breakout role of sorts, as the lead in Paramount’s “Lifeguard,” from 1976.

Sometimes his career leapt forward despite himself. He almost turned down a prominent part, as Cher’s lover, in “Mask” (1985), because he and Ms. Ross were in Hawaii on their honeymoon when casting began. “I can’t come,” Mr. Elliott told his agent by phone. That night, Ms. Ross quietly slipped away to call back the agent, telling him not to worry, that she’d get her husband back in time.

During fallow career periods, Mr. Elliott cashed in on his rich baritone, doing voice-overs for, among other advertisers, Ram Trucks, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association and Coors. He was always smart with his money, he said, and a saver, which let him appear in the three indie films this year, to his great satisfaction. In them, he feels he’s done his best work in ages. The one thing he still dreams of doing is singing in a stage show; he passed on a chance to be in “Annie Get Your Gun” with Reba McEntire years ago, and is still haunted by it. “I’d love to do a musical,” he said, “I could pick it up real quick.”