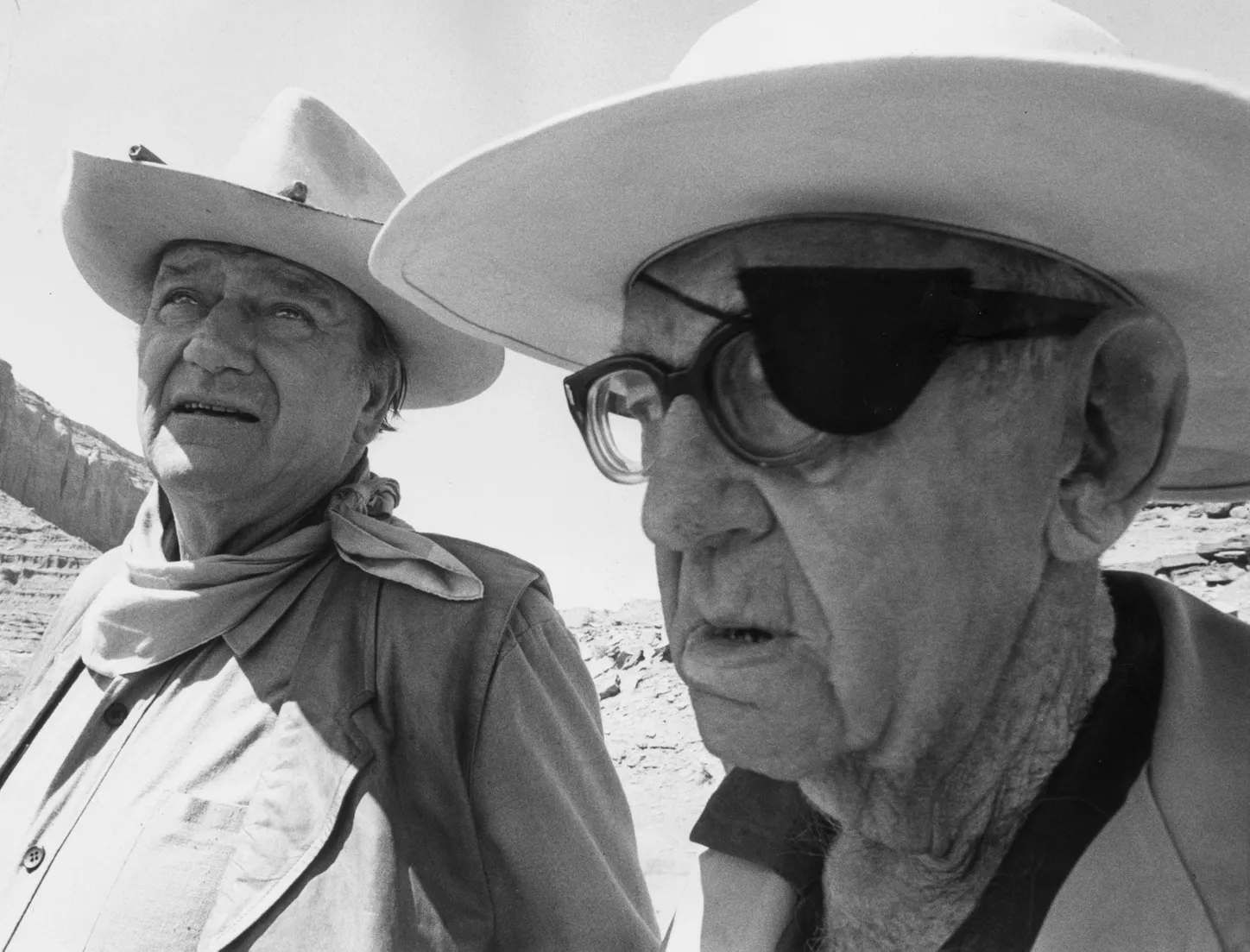

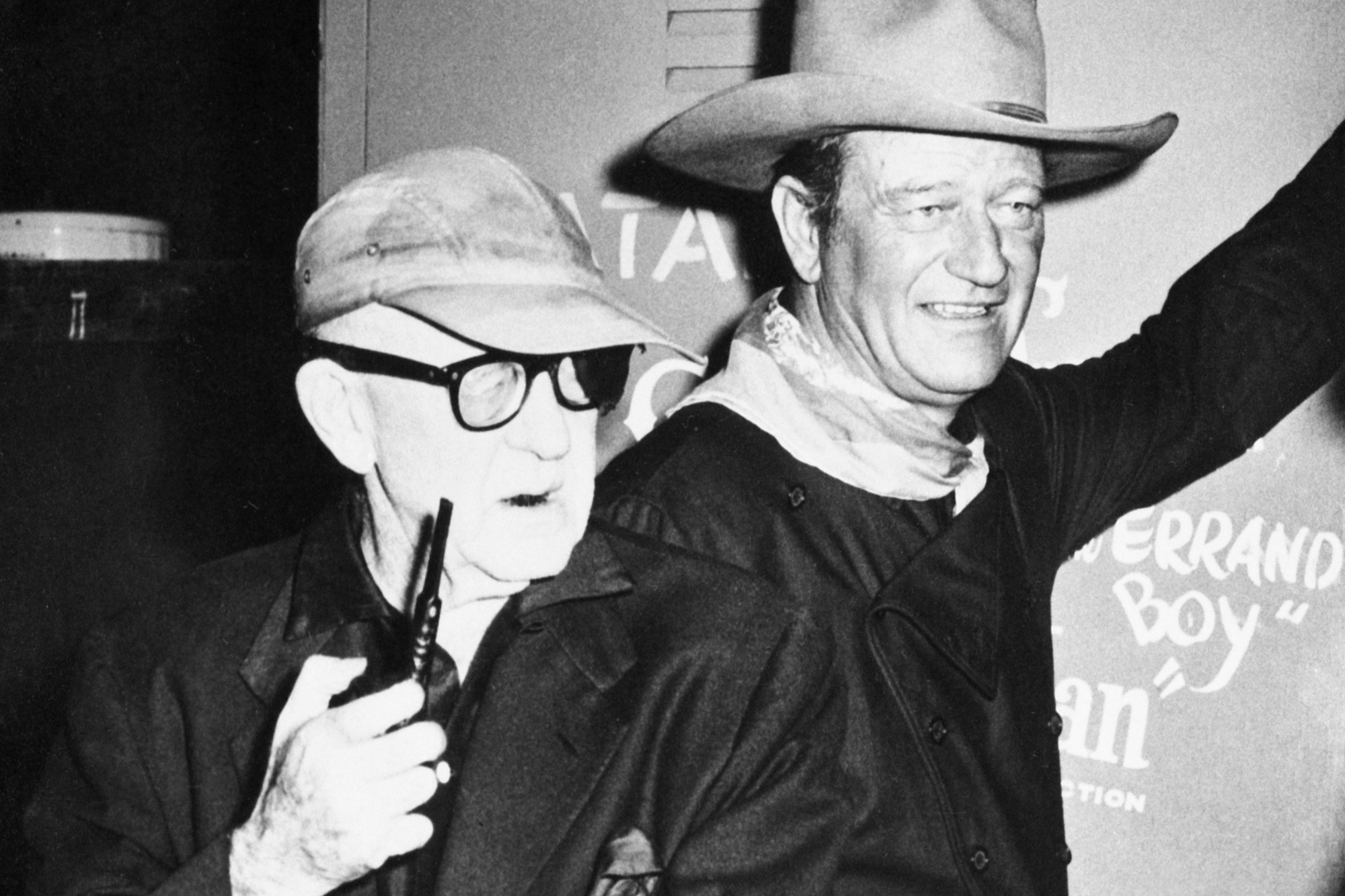

I’ve been reminded that, in my earlier column on what to me were three glorious days spent in the company of John Wayne, I said that there is more to the story. Here’s what I meant:

I hurried through all my duties in shooting my special to hang with my new friend as much as possible. Just at this moment of typing I’ve identified the feeling I was having then. It was as if a 7th grader (me) had been befriended by the popular, big, tall, jock upperclassman. And wished everyone could see us together, maybe with his hand on my shoulder.

(Did anyone just reach for an airsick bag?)

The picture, “The Shootist,” was his last. There is debate still about whether Wayne knew at the time that he — like the legendary gunfighter he was playing — was dying of cancer. Most agree that he did.

Here was a greatly talented, highly intelligent, college-educated, well-read man of immense personal charm and humor. I think we can agree that he knew.

There’s a rough-going scene in which he asks Jimmy Stewart, playing his doctor, not to spare him the details of what will happen as the disease progresses. It’s fascinating, if true as some say that he had not been able to do this in life, but — by requesting that the script be sharpened in detail on this point — chose this route to the information.

If I had to pick 10 highlights of my life, one would be my arrival on the set at almost the instant this scene was shot in the doctor’s office. The crew knew their long-time friend was not well. There seemed to be more people than usual standing around watching. When Stewart delivered the line with the dread word in it — the one even doctors will euphemise, as in “ca. of the breast” — a burly stage-hand-type near me had to quickly cover his mouth, apparently fearing that the sort of tearful, involuntary snort he emitted might have been picked up by a mike, spoiling the take. Similar moments on the part of crew members could be seen all around.

A second consequence of my time on the set with John Wayne: It’s early afternoon on the Western town square set. Costumed extras relaxing, smoking, gossiping, strolling, reading trade papers, Wayne off somewhere resting, napping or playing chess during a long break. (I can eye-witness report this: during breaks he shed his boots and slipped into a chartreuse pair of those fluffy marabou slippers more associated with women. Ludicrosity rampant. Probably a custom-made joke gift from a colleague. Or taken off a very large lady.)

A lone horse was at the hitching post. A huge horse. I had a sudden semi-rational urge. “Is that Dollar?” I asked. And I got onto John Wayne’s horse. To my surprise I find that I’ve recounted this sorry tale before, in this very paper in 1998. Reading it again scares the chaps off me, so suffice it to say that by the time Dollar’s spine-punishing trot had escalated into something more hazardous, then de-accelerated from there, and I was returned, trembling, to terra firma, there’d been a great deal of yelling from the crew and scattering of sun-bonneted extras (one clarion voice sounded above the rest: “Who the —— is that on Duke’s horse?”) and I was in a position to state for the record that an eternity lasts about 45 seconds.

I had one more glorious day with Wayne. He had agreed to appear on my special, and as I sat beside him — he in full costume — on a buckboard, with me holding the reins, in one hand, he said, “Are we rollin’?” At “Yes,” he took my hand mike and said into it, “Hi, this is John Wayne interviewing Dick Cavett.” (Don’t let me awaken, I thought.) We had a good time, and I might be able to retrieve this one for a future column.

The sun was up and the sky still bright but it had gotten to the time in the afternoon when the light changes undesirably for color film. I asked if they had finished shooting for the day.

“Yeah, it’s gettin’ a little yella.” (I won’t force the symbolic poignancy of those words.)

When we parted, I told him as best I could what a good time we had had together and what it meant to me. I said I felt kind of foolish, asking for an autographed photo.

“That shouldn’t be any trouble.”

He called for one, wrote on it, and without showing it to me, put it in an envelope.

We talked for a while more, mostly about the current prices of Indian artifacts, which I had seen swoop suddenly upwards. I asked him if he owned the beautiful beaded and long-fringed plains rifle case — probably Sioux or Cheyenne — he carried in John Ford’s “The Searchers.”

“I wish you hadn’t said that,” he said, grinning. “I bet I’ve thought about it a hundred times. I can’t watch the picture because of it. I tried later to find it, but somebody smarter than I am must’ve gotten it.”

“Didn’t it occur to you, maybe on the last day, to just slip it into your duffle bag?”

“It does now.” (Laughter.)

Having said goodbye and still aglow, while driving on the freeway, I remembered the picture. Pulling over like a responsible citizen, I slipped it out of the envelope, hoping there might be more than just the traditional “Best wishes” and a signature.

It read: “To Dick Cavett from John Wayne.”

This, of course, was enough. But below it there was another line.

“We should have started sooner.”

You bet I cried.