John Wayne made a lot of movies with a lot of actors, starring alongside the likes of Jimmy Stewart, Dean Martin, Robert Mitchum, Maureen O’Hara, Kirk Douglas, and Katherine Hepburn, and that barely even scratches the surface of the stars he worked with. Despite this, Wayne’s best co-star is actually a horse named Dollor, who was with him in all of his Westerns from 1971’s Big Jake until his retirement. Their partnership culminated in Don Siegel’s The Shootist in 1976, when Wayne insisted on script changes so that he could call the horse by its name, finally passing Dollor on to a young Ron Howard.

John Wayne Didn’t Like Horses

There’s a quote that Wayne gave biographer Michael Munn in his book, John Wayne: The Man Behind the Myth — “I’ve never really liked horses and I daresay not many of them liked me too much.” It seems an odd feeling to have for the most famous Western star in the history of Hollywood, but even from the time he was riding his family’s horse Jenny to school, Wayne (who at that time went by his birth name of Marion Robert Morrison) never particularly liked horses. Throughout his lengthy career, Wayne rode a whole host of horses, starting with Duke the Miracle Horse in his early career B-movie westerns. Often actors would just ride whatever horse the studio gave them, however a hallmark that would stick with Wayne, who at 6’ 4” was a large man, was tall horses. The notable outlier of a small Appaloosa named Zip Cochise in El Dorado really highlights that he needed a big horse.

Is it Dollar or Dollor?

In the later stages of his career, The Duke found a horse that would be the last one he would ride in a movie. There is a lot of conflicting information swirling around about what movies this particular horse was in, but unfortunately IMDb doesn’t have a list of credits for horses, making it a little tough to pinpoint where it all started. It’s even pretty tough to tell if the horse was named Dollar or Dollor. A lot of sources claim that 1969’s True Grit was the first to feature Dollor, not throughout the bulk of the movie but at the end after Wayne’s character Rooster Cogburn has to replace Beau, who dies in the climactic shootout.

While he does indeed get a new horse, and one that looks very similar to Dollor, it is actually a different horse completely — adding to the confusion, this horse is possibly named Dollar. Beau had a distinctive wide white blaze down his face with a small deviation over the right eye, so when Cogburn turns up with a new sorrel gelding with a thin white blaze many think this is Dollor, however the blaze is wider at the top on this horse’s face and gets thinner towards the nose, while Dollor’s starts thin and gets wider at the nose.

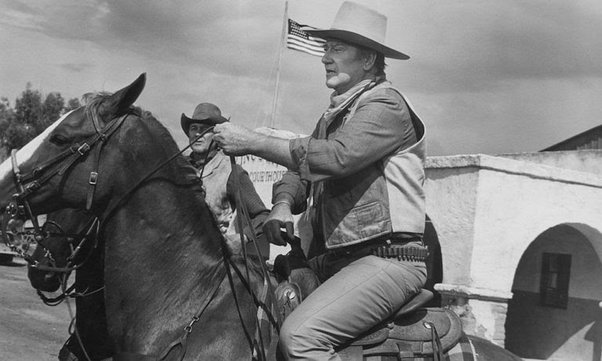

Beau is the mount Wayne uses in his next few Westerns, but it is in the 1971 George Sherman film Big Jake that Dollor made his debut. He is then featured in every western that Wayne makes until his retirement, namely The Cowboys, The Train Robbers, Cahill, Rooster Cogburn, and The Shootist. It’s interesting that it was in this late stage of his career that Wayne became so strongly taken with a horse when he had been riding them his whole life. According to a Chicago Tribune article, Wayne was so enamored with Dollor that he had a contract drawn up with the owner, Dick Webb Movie Productions, to ensure no one else could ride the horse on film. Wayne also stipulated that the script for The Shootist be changed to allow him to refer to Dollor by name, specifically calling him Ol’ Dollor repeatedly.

John Wayne’s Twilight on Film

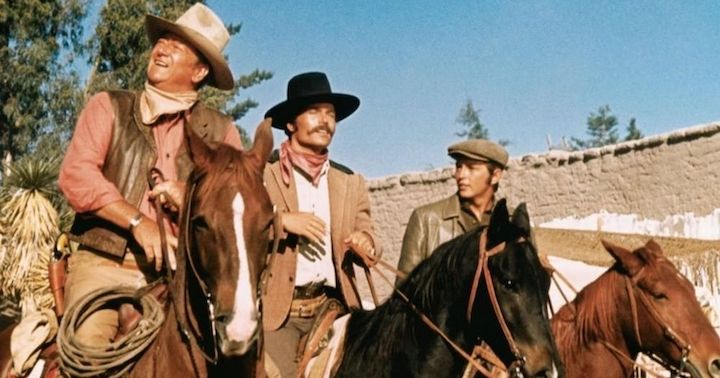

Many of Wayne’s final films share similar themes of family, legacy and a reckoning with an inevitable end, while also being among his best. In Big Jake, The Duke plays an estranged husband and father, pairing with not just his real-life son Patrick Wayne (something he did often), but also with his younger son Ethan Wayne playing his abducted grandchild.

In Rooster Cogburn, he plays a man that hasn’t evolved with the times and has been left behind by a society that thinks it no longer needs him. In some ways it’s fitting that he grapples with this in a sequel to True Grit, for which he won his only Oscar. It’s also interesting that Marshall Cogburn is the character who is least like the classic John Wayne persona, yet it wrestles with themes so pertinent in the way the film business had moved beyond what he offered. He also dies on-screen twice on film in just four years, which perhaps doesn’t sound like much, but it only happened nine times in almost half a century.

The film that most poignantly captures and mirrors the final years of The Duke’s life is his last, The Shootist. The movie is a surprisingly wrenching experience as an aging gunfighter (or shootist, as is frequently used) comes to terms with his imminent death from cancer and what his legacy will be once he is gone. When he gets the diagnosis from a doctor played by his long-time friend, Jimmy Stewart, he asks if he can cut it out. “Not without gutting you like a fish,” is the reply.

It’s impossible to separate this from Wayne’s own battle with cancer, the first occasion being in 1964 when his diagnosis of lung cancer led to the removal of his left lung and a couple of ribs. The Duke would later die of stomach cancer in 1979 — something that many have attributed to the filming of The Conqueror. The way his character, J.B. Books, is received in the town in which he chooses to die is a mixture of awe, fear, and animosity, as his reputation and legend precedes him. Again, hard to separate the character from the actor, especially when the opening includes a montage of footage from previous Wayne films.

Throughout The Shootist, Dollor plays a small but crucial role, becoming a central part of the relationship between Books and his short-term landlady’s (Lauren Bacall) son, Gillom (Ron Howard). As soon as Gillom discovers that the man that moved into his house is the famous shootist, from markings underneath the saddle on Dollor, the young man is obsessed. As the film progresses and people try to make their name by taking out Books, Dollor is a constant touchpoint for Books and Gillom, with the young man alternating between feeding the horse his oats and trying to sell him out from under Books. As their bond grows, it ends with Books giving Dollor to Gillom the night before his death. Just as the film climaxes on a nod between the pair, The Duke closing out his career by passing his favorite horse to a young star like Howard seems like a fitting way to go out.