John Wayne has earned his status as the King of Hollywood Westerns with his nearly unbelievable quantity of outlaw stories. Wayne’s filmography is essentially a catalog of how the genre evolved; 1939’s Stagecoach launched many of the archetypes that would last for generations, 1956’s The Searchers represented a growing maturation that reflected more serious ethical issues, and 1962’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance explored the end of the era as gunslingers reflected on their place in history. Wayne’s work was largely ignored by the Academy Awards, but his one and only Oscar win for Best Actor was for the iconic western True Grit. It was only fitting that Wayne’s final screen appearance would be in a Western, but The Shootist is an essential film regardless; both a reflection on Wayne’s career and a study of the cyclical, all-consuming nature of violence that he had been so eager to distribute.

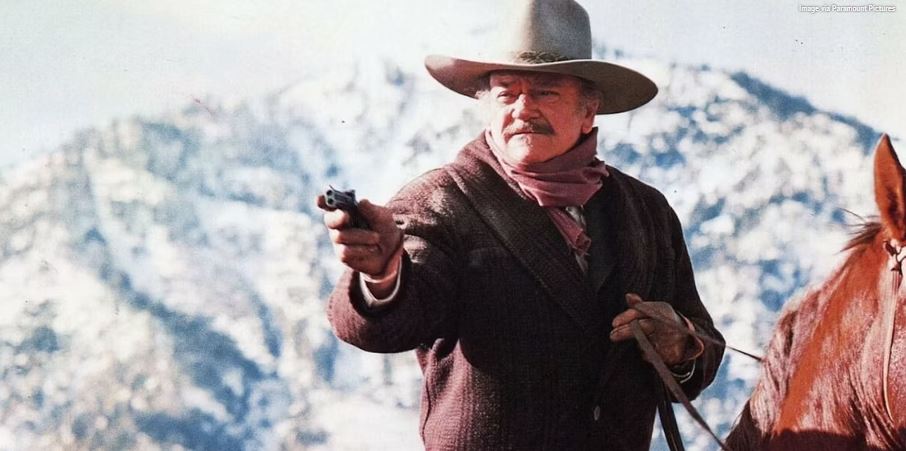

Directed by Dirty Harry franchise director Don Siegel, The Shootist casts Wayne as the aging gunslinger J.B. Books, who has essentially retired from duty. While Books does manage to take down a burglar with lethal force in his journey to Carson City, the real intent of his journey is to receive consultation on his failing health. Considering that Wayne actually died only a few years later in 1979 after his final public appearance at the Academy Awards, it’s evident that the role was a very personal one fashioned for him specifically. Books seeks shelter in the home of the caretaker Bond Rogers (Lauren Bacall) and takes a romantic interest in her, but also becomes a paternal figure for her son Gillom (Ron Howard), who has grown up without a father. In an emotional journey of reflection and possible redemption, Books seeks to settle down right before his heroism is called upon yet again. It’s a powerful story regardless of the man at the center, but The Shootist is even more impactful as a swan song for Wayne’s career.

In ‘The Shootist,’ John Wayne Gives a Matured Performance

Wayne had worked with an established series of directors throughout his career, but the grittiness that Siegel created was certainly a change of pace from some of his recent films, such as the heartfelt family film The Cowboys. Siegel’s creation of the Dirty Harry series indicated that he wasn’t afraid to show graphic violence, and at the dawn of the “New Hollywood” era, The Shootist was allowed to push the boundaries that John Wayne’s films had previously been barred from crossing. A later sequence where two assassins attempt to take Books out results in their shocking, violent demise with more intricate detail paid to their injuries and the specificities of their weapons. It was important to show the consequences of his actions, as the frequency of death in his films had drawn backlash. Wayne’s cold-hearted diligence during the exciting action scenes indicated that Books’ skills came from a lifetime of experience.

While Siegel succeeded in showing a more realistic depiction of what the fabled “Wild Wild West” actually looked like, it also gave Wayne a chance to show more sensitivity. His performance as Marshall Rooster Cogburn in True Grit was more of a caricature, but The Shootist is more specific in how it reflects Wayne’s history on screen. The opening flashbacks highlight Books’ past adventure and even use footage from Wayne’s previous films, tying the story together in an interesting way. It’s also quite touching that once he reaches Carson City, his first trip is to his longtime physician Doc Hostetler (James Stewart). Stewart was also among the most important figures in the history of the American Western and had been a frequent co-star and friend of Wayne’s. Seeing the two aging actors on screen together isn’t just a fun Easter Egg, but an encapsulation of the archetypes they had represented. Wayne is the gruff, no-nonsense drifter who pushes his physical capabilities, and Stewart is the kindly caretaker who grounds him in reality.

John Wayne’s J.B. Books Is a Terrific Character

Despite all of its disturbing moments, The Shootist is also one of John Wayne’s most heartfelt roles. He shows a vulnerability that hadn’t been seen in Wayne’s previous films, as his ego was notorious. Perhaps age had softened his heart because Books feels the physical toll that his work is placing on him. He’s also not celebrating his achievements; he goes to Carson City simply to live his last days in peace and takes discreet precautions to ensure that he won’t be identified. Tragically, none of Books’ efforts can hide his status. After giving Bond a false name and creating a fake headstone for himself, his legendary status as a gunfighter spreads quickly within the community as skeevy journalists, local officials, and prize-seeking bounty hunters all seek him out. Despite having a price on his head and the word from Hostetler that he needs to limit his physical activity, Books feels the need to find a second act as a family man.

To be fair, The Shootist wasn’t the only time that Wayne used a new Western film to reflect upon his career; given that Wayne was starring in new films (primarily action thrillers and Western adventures) up until his death. Even after True Grit won him the Academy Award, Wayne ended up reprising the role for the film’s 1975 sequel Rooster Cogburn. Unfortunately, his Western roles in the 1960s and 1970s were released during an era where Wayne’s brand of storytelling no longer felt cutting edge; he had already started appearing in neo-noir thrillers such as Brannigan and McQ to supplement his work within the Western genre. The Shootist couldn’t have come at a better time for Wayne; it was a film that refused to look at the past with rose-tinted glasses, yet still argued that the heroes of Wayne’s generation should be celebrated for their work.

Despite the similarities within the stories, The Shootist is not identical to the film it’s most often compared to – Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, which at the time appeared to be Eastwood’s final Western. While both films revolve around older gunslingers coming to terms with the decisions that they’ve made and reckoning with those that they left behind, the subtle differences between the two characters represent how far apart Wayne and Eastwood were as stars. While Eastwood generally plays darker, revenge-oriented antiheroes with little regard for anyone beyond himself and his select group of allies, Wayne’s characters at least try to start out with good intentions.

If Unforgiven was about a guilty man looking for an escape, then The Shootist presented the argument to the audience; Is Brooks justified in this situation, and could mentoring Gillom redeem some of his past sins? With mounting responsibilities and the pressures of growing up forcing Gillom to make rash decisions, Brooks knows that it’s his duty to show the young, impressionable boy a lighter path ahead of him. While obviously, the notion of a sequel would have been silly, it is notable that in real life Howard has heeded the lessons that Gillom did with his directorial work. When he began directing features of his own, Howard’s Westerns Far and Away and The Missing presented less glamorized versions of the West that didn’t lionize the era of gunslingers and killers.

‘The Shootist’ Is John Wayne’s Most Emotional Movie

The more emotional storyline in The Shootist comes from John Wayne’s character’s interaction with the Rogers family. In Bond, he finds someone he might foresee a future with, but he’s not aggressive in the way that many of his past characters were. His actions are to protect and comfort her, and his return to gunslinging is only to ensure that no harm comes to the city due to the criminals who are searching for him. The mentor role he plays in Gillom’s life is genuinely heartwarming, but it never becomes schmaltzy. Books teaches him the practical skills that he will need to survive and introduces him to his past associates and local troublemakers to show him the effect that the gunslinger lifestyle has. Regardless, the moment when Books gives his longtime horse to Gillom is incredibly touching.

Books’ grizzly death at the hands of a bounty hunter gang and final words of solace to Gillom are quite eerie, as he urges his young protege to remember the costs that this lifestyle has. Considering the gunfight had forced Gillom to use his gun and kill for the first time, it serves as a warning if he seeks to continue down this path. While a lesser director could have used this to indicate that Gillom would immediately fall into the same level of depravity that haunted Books during his adolescence, it’s clear from Howard’s shocked reaction that holding a weapon with the intention to kill is something that he never wanted to see again.

The Shootist is John Wayne’s last love letter to cinema, and there’s a lifetime of regret that perishes with Books. It’s a beautiful, haunting, and fitting end to the career of one of cinema’s most signature icons. Wayne is certainly among the most iconic movie stars of all time, but The Shootist makes the argument that he was also just a great actor who was willing to examine his past with a “warts and all” approach.