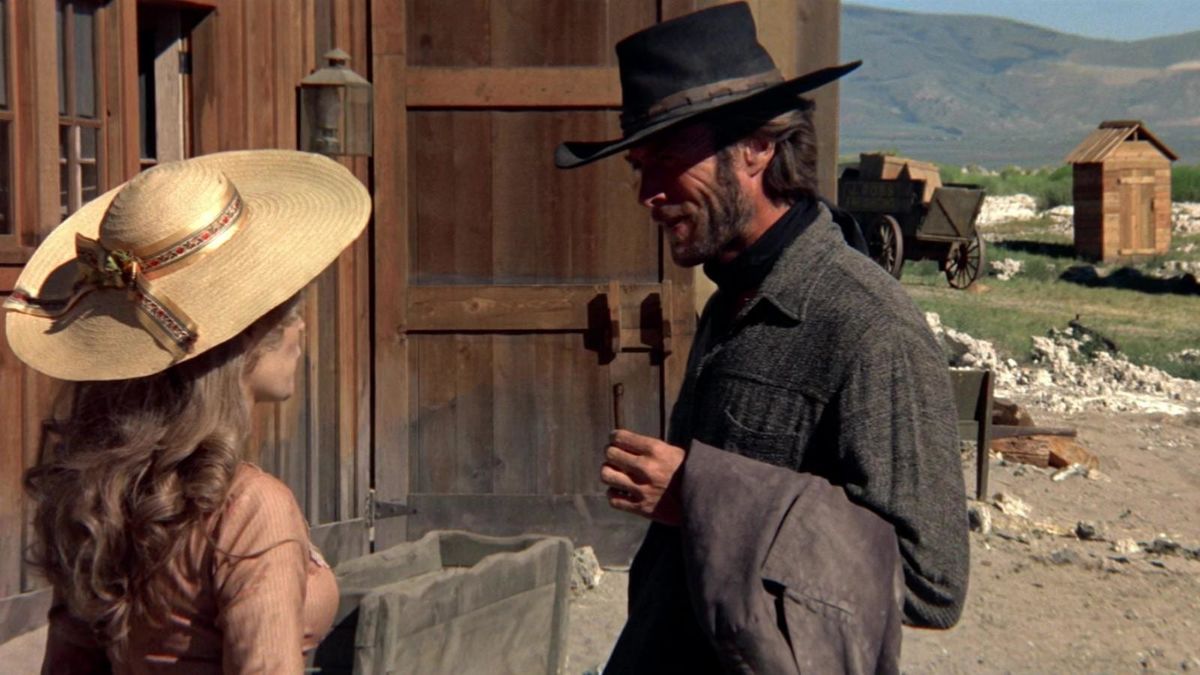

Clint Eastwood knew his way around a Western by the time he took it upon himself to direct one in 1973. “High Plains Drifter” is the follow-up to his filmmaking debut, “Play Misty for Me,” and, on the surface it appeared that the actor was giving his audience what they wanted. Eastwood stars as a man with no name who rides into a mining town seeking protection from a pair of outlaw families that killed their sheriff.

This might sound like a retread of “A Fistful of Dollars,” but Ernest Tidyman’s screenplay quickly veers from the formula. When the Stranger accepts the gig, he quickly takes advantage of the townspeople. He abuses two women, installs a bullied little person as the mayor and sheriff, and takes over the village’s only hotel.

The difference in “High Plains Drifter” is that the townspeople are anything but innocent. They hired the outlaws to murder the sheriff, who had learned that the mine largely responsible for the populace’s livelihood was on government land. Rather than pay the killers, they turned them in to the federal authorities. They’re now out of prison and seeking bloody vengeance.

“High Plains Drifter” was certain to rattle critics who viewed Eastwood’s Western collaborations with Sergio Leone as nihilistic and needlessly violent. It’s a cruel movie with a protagonist who makes The Man with No Name of the “Dollars Trilogies” look like Wyatt Earp. Eastwood knew Tidyman’s script would infuriate his detractors, so he opted to give the narrative a nasty little tweak that would turn the movie into a cynical morality tale.

The reaper rides into town

In a 1980 interview with Ric Gentry, Eastwood revealed that, in Tidyman’s original screenplay, his character was the brother of the sheriff. He thought this was a tad too, well, tidy, so he omitted this detail, and hinted at the Drifter’s motive. As he told Gentry:

“[T]he only clue is when the Drifter lies down (later in the hotel) and has this dream of the sheriff being whipped to death, and you know from there that he’s tied in some way, but you’re not sure how. That way you keep the mystique and the whole atmosphere is mysterious. To me, if the Drifter comes to town and immediately says, ‘I’m the brother of the murdered sheriff,’ right away you draw the conclusions. Instead, once he takes the town and humiliates them through his own methods, you’re asking, ‘Who is he? Why is he doing this?'”

The “why” is never plainly stated, but after the Drifter orders the townspeople to paint the town red prior to the arrival of the outlaws, and scrawls “Hell” over the village’s name as he rides out, you begin to get the picture. His closing exchange with the man he installed as mayor leaves little doubt as to the Drifter’s identity. “I never did know your name,” says the mayor. The Drifter’s chilling reply, “Yes, you do.”

Visually, Eastwood had a ways to go as a filmmaker, but his dim view of the United States and, to a larger extent, humanity has never been more emphatically expressed. We’re living on stolen land, and, as a later Eastwood character would inform us, we’ve all got it comin’.