It would surprise both his fans outside the United States (where most of them are) and his many American detractors to hear Charles Bronson, who has died of pneumonia aged 81, called a great actor. But if we accept that a camera-wise, if dramatically untutored, screen star may have a more deeply emotional impact – and stir even more complex emotions on a mass scale – than an Olivier or an Ashcroft, then a place may be reserved in the cinematic pantheon for him.

Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974), in which he played a father seeking revenge for the murder of his wife and rape of his daughter, helped make Bronson an international star. But he got there the hard way.

His first break was in You’re In The Navy Now (1951), because he could belch on cue. And he greased up to play more Native American warriors – in Drum Beat (1954), Jubal (1956), Chato’s Land (1971), etc – than Iron Eyes Cody. But along the way he got better and better, not unlike Burt Lancaster, who also started out with a physique but little acting talent.

Bronson was shatteringly effective in the low-budget Machine Gun Kelly (l958), and memorable in two under-rated films, The Mechanic (1972) and Hard Times (1975). The Mechanic, which most critics hated as disgustingly violent, is in fact a cold-hearted, meticulous study of male (homo?) sexuality dramatised in the ambiguous relationship of Bronson, a sybaritic professional killer, and his would-be apprentice and son-figure, Jan-Michael Vincent.

In Hard Times, he superbly played an ageing prizefighter punching valiantly to save his gambling manager, James Coburn, from a Mob beating. It was a dark, accurate view of the lumpen working-class life that Bronson, a coalminer’s son, brought bleakly and brilliantly to life.

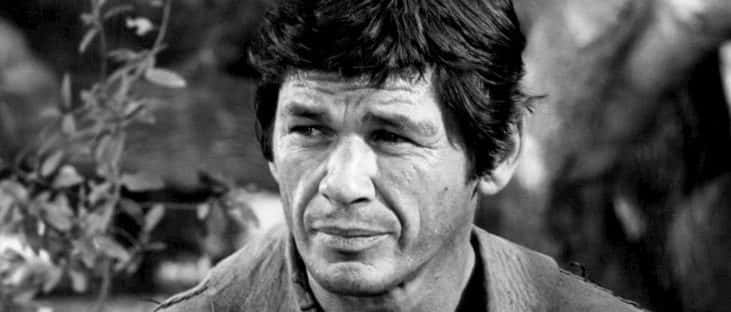

Part of Bronson’s problem was that he looked wrong, spoke wrong and appeared in all the wrong movies to impress the critics – even though cinema audiences could not get enough of his leathery face. He looked like a homeless drifter, talked as if he had just got off an immigrants’ boat, and moved like the bar-room brawler he often played. As he put it himself: “I guess I look like a rock quarry that someone has dynamited.”

In the right hands, as in Mr Majestyk (1974), he could be a wonderfully appealing working-class hero. In a strange, remarkably imaginative western, The White Buffalo (1977), he was completely in tune with the lyrical atmosphere. Until Death Wish, which inaugurated for him and Hollywood an ugly era of mean and dirty violence, he had carved out a niche as a tough, trim character actor in such films as The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Dirty Dozen (1967) and The Battle Of The Bulge (1965). Against type, he even clumsily played a beatnik artist in Elizabeth Taylor’s weepy The Sandpiper (1965), with Richard Burton.

But Bronson was not bankable until the French actor Alain Delon invited him to co-star as an American mercenary in the thriller Adieu, L’Ami (1968), which grossed $6m in France alone. European audiences went wild for him. That year also saw him in Sergio Leone’s tribute to a vanishing genre, Once Upon A Time In The West, where his unblinkingly studied performance as a harmonica-playing Mexican peasant bent on revenge is highlighted by Ennio Morricone’s haunting score. Again, in 1971, he packed foreign cinemas with Red Sun (Soleil Rouge).

From then on, Bronson prospered, even as critics ignored or assailed him. The coalminer’s son bought a 33-room Bel Air mountaintop mansion and a 260-acre estate in Vermont – a nice life for Charles Buchinsky, the 11th in a desperately poor Russian-Lithuanian family of 15 children, born in the Scooptown district of Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania. At l6, Bronson went to work in the mines, where he was paid $1 for each ton of coal he dug. He might have stayed there except for a second world war draft. He claimed to have been a B-29 tail gunner in the Pacific, but actually drove a delivery truck in Arizona.

Somehow, painting scenery led to small acting parts, and he hustled his way to California and enrolled at the Hollywood-prone Pasadena Playhouse. There he began the hard climb, playing minor hoodlums and Indian chiefs.

Bronson’s first marriage, to Harriet Tendler, produced two children and ended in divorce. In 1968, he married the actor Jill Ireland, who co-starred in a number of his films, notably Assassination (1987), where he is a secret service guard to her presidential first lady. She brought two sons from her first marriage, to David McCallum; Bronson and Ireland had a daughter, and their adopted son died in 1989. Ireland died of cancer in 1990, and, in 1998, Bronson married another actor, Kim Weeks. One of his favourite hobbies was painting. Before his death, he had been ill with Alzheimer’s disease.

Bronson was one of the last American film stars whose rough, unhandsome face actually spoke of experiences beyond a movie set. The way he looked, and his Scooptown-accented diction, brought a credibility, at times even a bleak grandeur, to his best roles that most of today’s young actors can only pretend to.