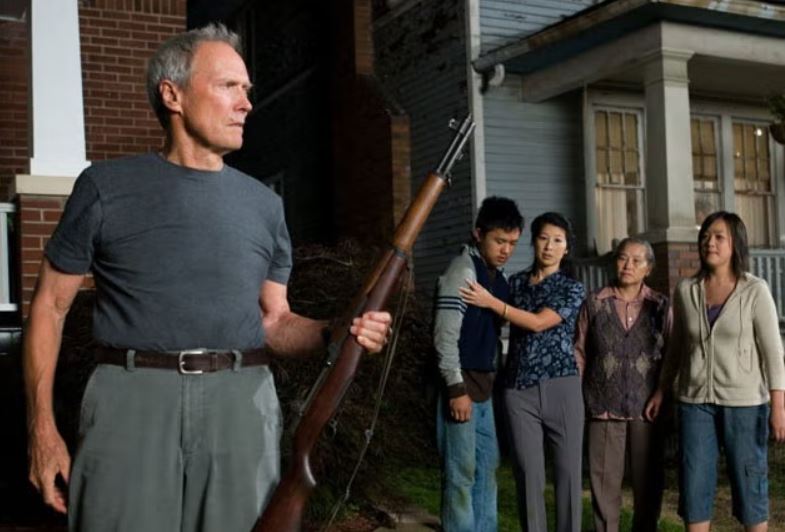

When screenwriter Nick Schenk started developing the story that would become “Gran Torino,” he was packaging VHS tapes at a factory in Bloomington, Minnesota. It was there that conversations with his many Hmong coworkers inspired the idea for a film about a bigoted white man developing an unlikely friendship with a Hmong youth. This cultural collision was eventually what led to Clint Eastwood taking the director’s seat and taking on the role as its lead Walt Kowalski. As for the rest of the cast, there was a push to find Hmong actors to boost the film’s realism. That proved a difficult task for casting director Ellen Chenoweth, given the lacking of representation of Asian groups in Hollywood.

Despite efforts to find Hmong actors like Bee Vang — who played the youth Thao Vang Lor — the representation in “Gran Torino” is not without controversy. The film has generated crucial conversations about the distortions that occur when non-Asians are the ones dictating Asian stories and characterizing their identities. Yet it all began with a single good intention gone awry: to increase the visibility of the Hmong people and culture by casting them in such a large production. And it started with Chenoweth spearheading outreach in Hmong communities for ripe talent.

Clint Eastwood Didn’t Cut Any Corners Casting Gran Torino

When screenwriter Nick Schenk started developing the story that would become “Gran Torino,” he was packaging VHS tapes at a factory in Bloomington, Minnesota. It was there that conversations with his many Hmong coworkers inspired the idea for a film about a bigoted white man developing an unlikely friendship with a Hmong youth. This cultural collision was eventually what led to Clint Eastwood taking the director’s seat and taking on the role as its lead Walt Kowalski. As for the rest of the cast, there was a push to find Hmong actors to boost the film’s realism. That proved a difficult task for casting director Ellen Chenoweth, given the lacking of representation of Asian groups in Hollywood.

Despite efforts to find Hmong actors like Bee Vang — who played the youth Thao Vang Lor — the representation in “Gran Torino” is not without controversy. The film has generated crucial conversations about the distortions that occur when non-Asians are the ones dictating Asian stories and characterizing their identities. Yet it all began with a single good intention gone awry: to increase the visibility of the Hmong people and culture by casting them in such a large production. And it started with Chenoweth spearheading outreach in Hmong communities for ripe talent.

Difficulties finding Hmong actors revealed a disparity in Asian representation

When Chenoweth started poking around for Hmong actors she quickly realized not many were members of the Screen Actors Guild. It was, after all, 2008, and examples of the kind of Asian-led films like “Crazy Rich Asians,” “Minari,” or “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” were far and in-between. Chenoweth said in a behind-in-the-scenes interview the search involved “a lot of digging.” She continued:

“A lot of getting to know the Hmong communities, making inroads, gaining their trust, and finding out who wanted to be in a movie. It wasn’t done through the normal channels. This was really going to them and opening ourselves up to them.”

Her digging proved fruitful however when — assisted by cultural advisor Cedric Lee — they met with leaders in Hmong communities in Fresno, California, and St. Paul, Minnesota. “We’d go to places where Hmong people hung out,” Lee recalls of their efforts to get the word out. “We went to Father’s Day parties. We went to church events. There’s a language barrier, especially for the elders, so we would speak Hmong and then translate to the casting directors. With the youth, it’s a lot easier because a lot of them are English-speaking.” All of it came together when they held a massive day-long open audition for “Gran Torino” in St. Paul — the very same city that the soon-to-be discovered Vang was himself from.

Finding the Eastwood’s costar Bee Vang

After hundreds of audition tapes, one picture started to stick in Chenoweth’s mind. “He had very little acting experience, but had this quality that was so open and sweet,” she said of the 16-year-old Vang. “You just wanted him to be okay.” Ironically enough, the actor revealed in a talk recorded in the Hmong Studies Journal he was initially reluctant to audition because what he’d heard about the story had “repulsed” him.

“I never thought I would try out. I heard about the story and the ‘sides’ – the excerpts from the script that were used for auditions – and I was just really repulsed by what I read. I tried to make sense of the characters and their lines. But there were things I couldn’t figure out about the relations between Walt and the Hmong characters. For instance, at some point Thao tells Walt ‘Go ahead. I don’t care if you insult me or say racist things, because you know what? I’ll take it.’ I didn’t understand why a character like Thao would say that. Why wouldn’t he object to being insulted? What does ‘taking it’ even mean? What was intended by the screenwriter or was this just careless writing?”

Despite his concerns that the Hmong were being viewed through a racist and emasculating lens, Vang eventually auditioned because of peer pressure. But over time he started to see “Gran Torino” as an opportunity to create a meaningful portrayal of Hmong characters: “I wanted to create a character that people could love. I decided to commit to developing the role of Thao, making him more complex and credible.” Unfortunately, according to Vang, time has only made it more lucidly clear that the film did more harm than good.

Vang’s views of Gran Torino grew more critical over the years

Since “Gran Torino” was released, Vang has been one of the loudest advocates against the film. Writing for NBC last year about upticks in attacks against Asian-American communities, the actor said the film had “mainstreamed anti-Asian racism, even as it increased Asian American representation.” Given that even today there are reckonings with racist portrayals in popular films like “Licorice Pizza,” it’s a conversation that hasn’t stopped. In an op-ed from 2011, he detailed how he started to reckon with the film’s harmful portrayals.

“After Gran Torino’s release, Hmong around the country were furious about its negative stereotypes and cultural distortions. I know this acutely because when I spoke at public events, they came out to confront me. I found myself in the awkward position of explaining my obligation as an actor while also recognizing that, as a Hmong American, I didn’t feel I could own the lines I was uttering.”

To make matters worse he also revealed that both his and the Hmong cast’s concerns were often undermined and not taken seriously. “I reminded my critics that this was a white production,” Vang explained. “That our presence as actors did not amount to control of our images.” It’s a recurring theme in productions about minorities led by predominantly white men. But it begs the question of why go through all the trouble of finding a phenomenal Hmong cast if you’re just going to pigeonhole them in damaging stereotypes?

Is Gran Torino about the Hmong people at all?Warner Bros. PicturesAs a result of those stereotypes, Vang questions both why and if “Gran Torino” is even a film about the Hmong at all. Not only did the film’s white savior plot invalidate much of Thao’s journey to manhood, but it was also clear that despite wanting Hmong actors Eastwood wasn’t interested in contributions that didn’t fit stereotypes. Vang said in the Hmong Studies Journal:

“I know there were a lot of Hmong references and scenes in the film, but I didn’t feel it in my character. What I felt was being called on to perform the pan-Asian stereotype of the submissive, kow-towing geek with no girlfriend. Plus there’s no real reason for us to be Hmong in the script. We could be any minority. And not only that, but Walt is always confusing us with Koreans and other Asians. Even with the enemies he fought in Korea. So Hmong culture, Hmong identity didn’t end up seeming so relevant.”

The Minnesota Post reported that inaccuracies were just as rampant. Scenes that depicted it as unorthodox to touch someone’s head or the wearing of traditional Hmong clothing to a funeral are just two examples of the liberties Eastwood took.

The film also doesn’t even explore facts about Hmong history that Shenk learned from his coworkers: supporters of the U.S. in Vietnam, many left their homes in Southeast Asia and China after communist uprisings in Laos in 1975. When America pulled out, the Hmong were forced into refugee camps. Nowhere in “Gran Torino” is this history or any aspect of Hmong culture seriously explored. As Vang has stated numerous times the film instead relegates the Hmong to a superficial presence that exists only to give Eastwood’s prejudiced character an opportunity for heroics.