Westerns have existed since the dawn of cinema, but by the 1930s they were considered B-pictures. Major studios at that time refused to put up big budgets and major stars for films set in the wild west. That didn’t stop director John Ford. Struggling against this lack of mainstream interest in the genre, Ford moved from one producer to another in order to get 1939’s Stagecoach made.

After years spent honing his craft in the movie business, Ford finally came into his own with this film—as cinema’s premier western director, destined to later create such classics as The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. With Stagecoach, Ford breathed new life into the western, treating the genre with a seriousness it had not yet felt. The film consequently became something like the genre’s blueprint for years to follow. It is due to its artistry, socio-psychological elements, and claims to the American myth that Stagecoach proved highly influential.

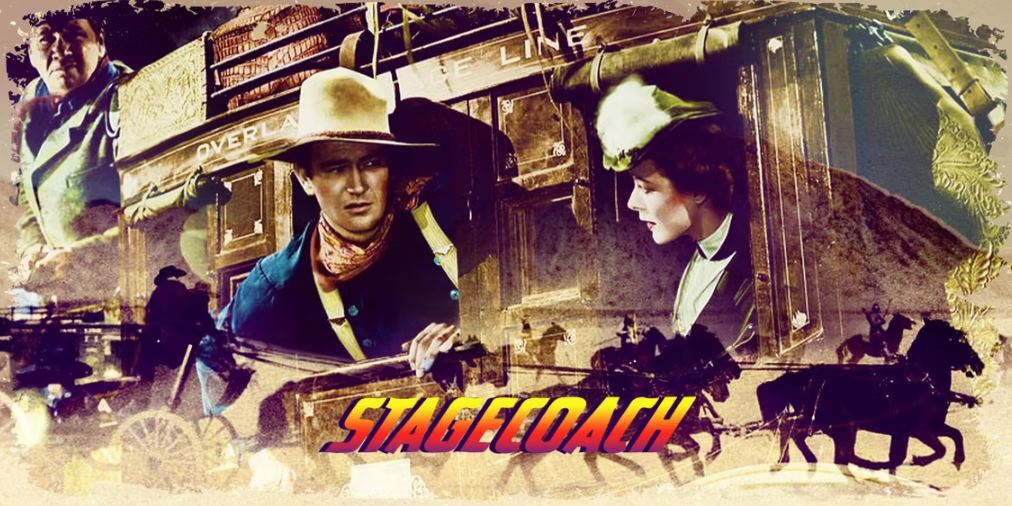

The film stars an ensemble cast of characters, fronted by John Wayne in the role of outlaw Ringo the Kid, as they travel turbulent territory in the titular stagecoach from upscale Tonto to seedy Lordsburg. Like Ford, Wayne had been in the industry for years without success, and this would be the role that established his stardom. It also established his typecast, with Ringo the exact type of lonely-cowboy-antihero role Wayne soon wouldn’t be able to escape. It’s not hard to see why he left such an impression here. Wayne is an unforgettable presence as Ringo, moseying around and drawling his speech so casually that it always manages to be a shock when his morals are revealed to be so upright and noble.

Ringo is travelling on the coach to avenge the murders of his father and brother. The foe who did it is waiting to duel him in Lordsburg. All the other characters in the coach have their reasons for travel. Dallas (Claire Trevor) was run out of Tonto for prostitution. Curley (George Bancroft) intends on turning in the wanted Ringo at Lordsburg. Lucy (Louise Platt) is pregnant and hoping to meet up with her soldier husband, while conniving gambler Hatfield (John Carradine) intends on protecting Lucy along the way. Ford manages to give scenes a richness by stuffing in so many characters, each with conflicting goals and values, that there’s always another perspective to consider.

This never becomes the muddled mess that it easily could, however, because of the precision and clarity with which Ford films these characters. The film is lyrical in its economy, only giving the audience the necessary information from scene to scene with little excess. Oftentimes a plot development will hit, and then each character is given just enough time to react in a way falling in line with what the viewer has already learned about them. In this manner, the plot can move forward while the characters are strengthened, and neither has to detract or distract from the other.

Though in a sense many of these characters conform to stock archetypes (from the hooker with a heart of gold to the lonely and misunderstood outlaw-rebel), they are each conflicted and complex. It’s not easy to define each as strictly a hero or a villain. Ford’s style is understated enough to see them with clear-eyed objectivity and yet empathetic enough to understand them, regardless of whether their decisions are admirable or not. Ringo, for example, is portrayed as a lowly outlaw who plays by his own rules, but also one who has an authentic love for Dallas and a consistent personal ethic.

As the film runs, the stagecoach becomes a microcosmic world, with the characters being used to explore serious social issues of class and prejudice. Dallas is looked down upon by the other passengers for her prostitution, and seemingly for her lower social standing in general. A particularly tense scene in a saloon has the majority of the passengers changing seats so they don’t have to eat anywhere near her. But Ford’s lens is humanistic. Just as it sees the kindness beyond her rough and streetwise exterior, it sees the well intentions and miseducation behind such intolerance on the part of the other passengers.

Unfortunately, this humanism is selective. The film is notorious for its barbaric portrayal of Native Americans. The central conflict of the film is that, in order to get to Lordsburg, the stagecoach must travel through land ruled by Apaches. They are portrayed as nothing less than murderous monsters on a warpath. One scene early on has the coach passengers stopping at an inn, only to find that the innkeeper’s wife is an Apache woman. She’s clearly harmless, and it’s played comedically that the passengers are so taken aback by her presence. Later, it’s revealed that the woman left to alert her fellow Apaches of the stagecoach’s whereabouts, so they can come in for the kill. In doing so, the film essentially confirms the passengers’ racist first impressions, suggesting that even the most innocent looking Native Americans are out for blood.

It’s an ugly and ultimately unavoidable aspect of the film, made worse by its long term impact. For years westerns were damaged by these hateful preconceptions of Native Americans, in large part due to the influential Stagecoach having depicted them this way first. As with other racist classics The Birth of a Nation and The Jazz Singer, a lot can be learned by looking into the mechanisms of these attitudes as they are expressed in the film. It’s important to see these films for this reason on its own, but one can’t deny their formal brilliance and cinematic influence simply because of this one regrettable element.

Case in point, the climactic scene in which the Apaches violently storm the stagecoach is among the film’s most masterfully crafted sequences. Ford applies his directness and simplicity of style to make for an action scene as exciting in its scope as it is easy to follow. Still, Ford doesn’t limit himself from including some particularly inventive camerawork for the time, such as a shot looking up from the ground in which fast-moving horses appear to tread over the camera.

The barren, rocky landscape of southern Utah is highlighted in this sequence, chosen by Ford as the location for the film so that he’d be far from any meddling studio heads. He would continue to shoot in this otherworldly desert for every subsequent western of his career, in a sense becoming his playground. The scene also contains much of the film’s death defying stunts by Yakima Canutt, which were performed without any special effects. When it appears as though he’s leaping from horse to horse while they run at high speeds, he was indeed doing just that on set.

Despite its hypocritical prejudices, Stagecoach cannot be dismissed. The power of its filmmaking clearly reveals just how it managed to elevate the western from B-movie status to one of the most popular and important genres in film history. The poeticism of its style and the deeply felt characterizations were enough to make it a classic, but the strength of the film did something more. It established the wild west as the stage for the great American myth. By showing that even something as straightforward as a stagecoach ride could become a thrilling adventure, that every passenger in such a coach could have such an interesting history, it forever made the world of cowboys and gunfights the ultimate dream of America.