There is no better Western film in the history of cinema than Sergio Leone’s 1966 masterpiece The Good, The Bad and The Ugly. While Stagecoach was largely responsible for launching the new wave of the genre’s popularity and The Searchers is often cited on critics’ lists of the best films of all-time, there aren’t a lot of moviegoers who aren’t familiar with Ennio Morricone’s famous, enthralling main theme from Leone’s classic.

Even for those who haven’t seen its two predecessors, A Fistful of Dollars and A Few Dollars More, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly is an electrifying thrill ride from beginning to end. It’s one of the rare films that spans nearly three hours and doesn’t waste a moment.

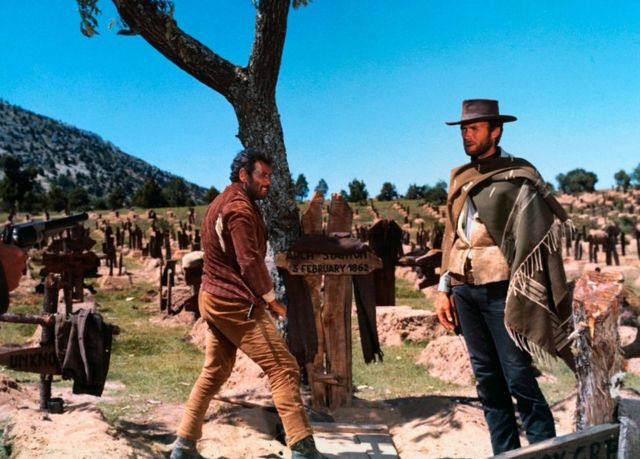

There are a lot of fantastic moments in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, and the film’s consideration of the ramifications of war and the allure of greed make it even more interesting on subsequent rewatches. However, the film is best known for its iconic standoff sequence when the pillars of heroism, villainy, and moral ambiguity square off in a three-way duel. The “good” is the stern bounty hunter “Blondie” (Clint Eastwood), the “bad” is the wicked mercenary “Angel Eyes” (Lee Van Cleef), and the “ugly” is the selfish thief Tuco (Eli Wallach).

You don’t have to look very far to see the influence of the scene on modern movies; even films outside the genre have taken inspiration from the duel. Marty McFly’s (Michael J. Fox) recreation of the moment is the climax of Back to the Future: Part III, and Jesse (Aaron Paul) faces a similar western-style duel at the end of El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie. Leone crystallized the “Spaghetti Western” craze in this signature battle, identifying clear archetypal characters that would inspire countless recreations, homages, and parodies. The creative, practical techniques used to bring it to life continue to give moviegoers memories today.

How Leone Crafted a Legend with ‘The Good, The Bad and The Ugly’

While The Good, The Bad and The Ugly was the third film in Leone’s “The Man With No Name” trilogy, it was actually a prequel, as the other two films were set before the Civil War. This gives the standoff scene an important function within the story of all three films; the quick-draw of Blondie is what makes him a figure of such legendary abilities by the time that his reputation is renowned at the beginning of A Fistful of Dollars. On a cultural level, it is most often cited as Eastwood’s most iconic moment. While the prior two films were successes, seeing Blondie face his enemies with such controlled confidence is what helped turn Eastwood into the most beloved Western film star of all-time.

While it’s renowned for being an epic of incredible scope, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly was only given a budget of $1.2 million. This necessitated Leone to be tactful in his filmmaking choices in order to make use of his sparse resources; he wouldn’t be able to create the type of spectacular extended shootout that westerns like The Magnificent Seven or Rio Bravo had done. As is often the case, filmmaking constraints bode well for innovation and creativity; the starkness of the shootout is one of the reasons it’s so intense.

Essential Collaborators on ‘The Good, The Bad and The Ugly’

Leone also knew that like its two predecessors, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

had to make use of Morricone’s great musical impulses. However, Leone wanted to make the standoff scene particularly haunting and serve as a proper climax to the three film narrative, and asked Leone to examine the cemetery where the scene takes place. Morricone remembered that he was told to imagine “the corpses were laughing from inside their tombs,” a particularly haunting concept considering the cold-hearted dark comedy of the film. This note proved to be essential; Morricone’s score intertwines more chilling, darker notes than the two preceding films.

It wasn’t just the music that made the standoff so haunting; Leone hired a crew of Spanish soldiers to put together a cemetery with several thousand gravestones and wooden crosses so that the characters were literally surrounded by death. Leone wanted the graveyard to resemble a Roman circus. This helped give the film a mythic, medieval style. It made sense, as A Fistful of Dollars had taken direct influence from Akira Kurosawa’s samurai film Yojimbo, another medieval epic about archetypal heroes and villains.

The Standoff Was an Unusual Shoot

The other collaborator essential to the film’s success was cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli, who despite not working on the other two “The Man With No Name” films had experience shooting Spaghetti Westerns. Leone had Colli prioritize the lighting so that the shootout would appear to be more mythic in nature. The choice to include so many close-ups of the characters’ faces was another request from Leone that proved to be essential; the tension rises to its peak as the camera moves like a whirlwind between Blondie, Angel Eyes, and Tuco as they consider their options and wait for each other to draw.

The slower pace didn’t exactly please all of the film’s stars; Eastwood was so annoyed with Leone’s perfectionism that he refused to star in his next film Once Upon A Time In The West. Eventually, he would cite Leone’s ability to draw audiences to more violent and morally ambiguous confrontations as one of his greatest strengths. Even if Eastwood didn’t star in it, Once Upon A Time In The West drew a direct influence from the standoff sequence during the climactic final duel between Charles Bronson and Henry Fonda.

While it’s been ripped off, recreated, and parodied countless times since 1966, the standoff in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly has yet to be topped. It was a bold way to end a film that essentially launched an even greater influence in Spaghetti Westerns that would attract a new generation of filmmakers to the medium; creators like Quentin Tarantino and Vince Gilligan often cite Leone’s influence on their work. While its unusual inception may not have seemed traditional at the time, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly broke the mold in its signature moment.